|

As such, the defence of

Brazilian sovereignty was structurally entangled with the

defence of the slavery system. At a purely diplomatic level,

from 1863

Great Britain had abandoned its efforts

aimed at the direct termination of slavery in

Brazil. Now, however,

Great Britain's

attention seems to have turned to undermining the foundations

of the Brazilian slave system by means of liberal propaganda

and free immigration. [13] It was around this issue that

Scully's altercations with Brazilian elites would centre,

subsequent to the Christie Affair. They appear to have been

the most profound reasons for the events of July 1868 and the

failure of British colonisation schemes in Brazil.

A Sabotaged Project: The Irish in Santa Catarina (1867-1869)

In 1866 some advances were made in some of the directions proposed by

Scully. The creation in

Rio de Janeiro

of the International Emigration Society, in February of that

year, had the direct participation of the Irish journalist,

despite all the criticisms he made of the profile of that

entity. [14] The Third of August Cabinet, inaugurated

that year, showed a disposition towards implementing some type

of effective mass immigration programme, reflecting the

growing perception that the war effort was bound to intensify

the country's labour shortage. Later on, Councillor Zacarias

determined, in November 1866, that the slaves owned by the

State ('slaves of the Nation') be emancipated for

military service, prompting the acquisition of slaves from

private owners for same purpose (Costa 1996: 244-248).

However, the

clearest proof that the slavery question was the object of

primary consideration in

Brazil

at that time is afforded by the Imperial Speech ('Fala do

Trono') that opened the first session of the Thirteenth

Legislature of the General Legislative Assembly on 22 May

1867. Addressing the issue, Dom Pedro II gave the legislators

the following message:

The Servile element in the Empire cannot but merit

opportunately your consideration, providing in such a manner,

that, respecting actual property and without a severe blow to

our chief industry - Agriculture - the grand interests which

belong to emancipation may be attended to.

Next, the

Emperor hinted that 'to promote colonization ought to be the

object of your particular solicitude' (Brazil. Federal Senate

1988-1: 264). [15]

It is of significance that the

23 May 1867 issue of The

Anglo-Brazilian Times featured a very enthusiastic

commentary by Scully:

Should

Europe pour in here her

superabundant population, where employment could be given to

20,000,000 of them, then the Government of Brazil can

emancipate the slaves without ruining the production of the

country and with some prospect of providing for the future of

the freedmen.

This was

preceded by a curious occurrence when, a few months earlier,

Scully had apparently been sent to jail. Following the

outbreak of a fire in the office of his newspaper, in February

1867, the Irishman had had a heated discussion with Chief of

Police Olegario Herculano Aquino de Castro, during the course

of investigations on the matter and the policeman arrested

him. The Emperor himself seems to have interceded and the

Chief of Police was exonerated. His substitute, however,

issued an order of imprisonment against Scully, who complained

about this with the Emperor's son-in-law, and heir to the

throne, Luís Filipe Maria Fernando Gastão de Orleans, Count

d'Eu (1842-1922). The order apparently was not executed. [16]

Meanwhile,

since 1866, the immigration of North American Confederates had

been on the increase. Having decided to leave the United

States after the Union's military victory in the 1861-1865

Civil War, the Southerners encountered in The

Anglo-Brazilian Times' editor a fervent collaborator and

publicist. An example of this can be seen in the editorial of

23 June 1866, when Scully praised the then Minister of

Agriculture, Antonio Francisco de Paula Souza (1843-1917), a

freemason. Scully noted that:

Brazil needed

only to be known to be appreciated as a field of emigration,

and, fortunately [...] the dissatisfaction in the Southern

States of North America caused Brazil to be visited by various

small parties of Americans deputized by various companies of

expatriating Southerners to seek homes wherever best for them.

The estimates vary greatly, but, according to Frank Goldman, around 2,000

Confederates settled in

Brazil, out

of approximately 10,000 people who left Dixie after the war

(Goldman 1972: 10).

Colônia Príncipe Dom Pedro also figured among the destinations of the

Confederates. Situated on the right bank of the Itajaí-Mirim

river in Santa Catarina and in proximity to another colony,

that of Itajaí (renamed Brusque), settled mostly by Germans.

Created by the Imperial Decree of

16 February

1866, Príncipe Dom Pedro colony began to be effectively

occupied by southern North American pioneers at the beginning

of the following year. Its first director was an American,

Barzillar Cottle. The amateur historian from Santa Catarina,

Aloisius Carlos Lauth, in his most valuable work about the 'Príncipe

Dom Pedro' indicates that, at the end of 1867, the number of

Confederates involved in the colonising project had reached

237, that is, 35.5% of the total. The number of Irish coming

from

New York

through the initiative of Quintino Bocaiuva was 129 (19.5%),

and that of English, 108 (16%). There were also, in smaller

numbers, French, Germans, Italians and others (Lauth 1987:

35). [17]

In 1866 Scully took the initiative of advertising

Brazil as a

prospective home for Irish emigrants. As well as writing a

book about all of the Brazilian provinces to serve as a guide

for immigrants (published for the first time in 1866 and again

in 1868), he twice published in the Anglo-Brazilian Times,

in October, a letter addressed to the Anglican Clergy in

Ireland, requesting the procurement of colonists to that end.

At the same time, in Brazil, the journalist continued to

intensify propaganda for Irish immigration:

The Irishman, perhaps justly accused of unthriftiness and

insubordination at home, for he is hopeless there and has the

tradition of a bitter oppression to make him feel

discontented, becomes active, industrious, and energetic when

abroad; intelligent he always is. He soon rids himself of his

peculiarities and prejudices, and assimilates himself so

rapidly with the progressive people around him that his

children no longer can be distinguished from the American of

centuries of descent (ABT 23 January 1867).

At the end of 1867, around 339 immigrants coming from

Wednesbury,

England, were ready to embark for Brazil (256 of them Irish)

(Marshall 2005: 56). Leaving England on 12 February

1868, and arriving at

Rio de Janeiro

on 22 April 1868, these immigrants were received in person by

Emperor Dom Pedro II. [18] They were subsequently embarked for Colônia Príncipe Dom Pedro, where Irish migrants were not well

respected because of the problems caused by compatriots of

theirs, from New York, who had settled there and were involved

in brawls and excessive drinking. Scully, noting the undue

interference by another immigration agent (Chevalier

Francisco de Almeida Portugal) in the undertaking, and

informed of the problems that awaited the new arrivals,

advised them not to go to the Itajaí-Mirim river valley (ABT

23 March 1868). [19] But it was too late.

When we turn our attention back to Scully's attacks against Caxias in

January 1868, we see that the chronology of events is quite

suggestive. It can be assumed the imminent embarkation of the

Wednesbury immigrants had lifted Scully's spirits, because of

his direct interest in the success of the undertaking.

Certainly, the apparent moroseness with which war operations

were being conducted in

Paraguay

during the period of the siege of Humaitá irritated him to the

extreme, because of the urgency he felt that the proposals put

forward by him since 1865 were successful. Therefore, the tone

of his diatribes against the Brazilian marshal were not in any

way gratuitous or extemporaneous. There was a great deal at

stake. The experience in the Itajaí-Mirim valley looked like

it constituted the first step towards the formation of a

demographic magnet, designed to attract more British

immigrants. [20] Therefore the fact that the necessary

resources for the promotion of immigration were being spent on

the war effort must have been quite exasperating. Actually,

after July 1868 and the deposition of Zacarias de Góes e

Vasconcelos, the new Conservative Minister of Agriculture

imposed severe 'budgetary cuts in the support of state

colonies, in part due to the mounting costs of the Paraguayan

War' (Marshall 2005: 78).

During the interval between the fateful article in the Anglo-Brazilian

Times of 7 January 1868 (along with other articles) and

the removal of the Third of August Cabinet in July, the

recently-arrived Irish people that eventually settled in

Colônia Príncipe Dom Pedro had to face the adverse conditions

anticipated by Scully, even though some preparations for their

accommodation had been made. Among them was the appointment,

at the end of 1867, of an Irish Catholic Priest, Joseph

Lazenby, to be responsible for the spiritual life of the new

colonists. Lazenby had been attracted to the colony when he

heard of the presence of Irish settlers therein (Marshall

2005: 75), and he even managed to convert the American

director Barzillar Cottle to Catholicism (Lauth 1987: 42-46).

The undertaking was frustrated, though, by a combination of factors, that

affected all the settlers attracted to it since the foundation

of the colony in 1866. A confrontation with the German

colonists of the rival colony of Itajaí, on the left bank of

the Itajaí-Mirim, resulted in March in the removal of Cottle

and in the subsequent nomination of directors hostile to

Anglophone settlers. The precariousness of roadways impeded

the transport of the produce of the colonists, many of whom

alleged not to have received payments for services rendered

for the infrastructure of the colony. The lots of land, all of

which were assigned with a considerable delay, were situated

in locations subject to flooding and torrents, which indeed

later occurred. With the removal of Zacarias' cabinet, from

July 1868 the colonists found themselves divested of any

political support during the Conservative era inaugurated by

Itaboraí. When the Itajaí-Mirim river burst its banks and the

colony was flooded, any chances for success for the project

were obliterated (Marshall

2005: 78).

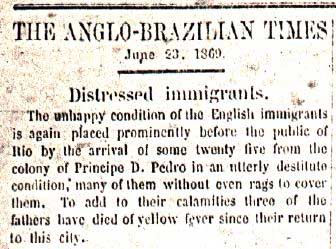

The Anglo-Brazilian Times, in its editions of June 1869, related

the arrival at

Rio de

Janeiro, in rags, of a group of Irish people who had left

Colônia Príncipe Dom Pedro. Equally, it gave notice that

members of the British community of that city had provided

help in purchasing return passages for the immigrants to

Britain and Ireland. On 19 June a list of donors was published

with their respective contributions, totalling £130, which

seems to have been employed in the maintenance of the

desperate immigrants. Gradually the colony was evacuated of

all English-speaking colonists, while the intervention of

British consular representatives in Rio and Santos prevented

an even worse outcome for the impoverished settlers, most of

whom were relocated in Brazil, Argentina and the United States

(Marshall 2005: 80-87). Many had lost relatives during the

venture. Finally, the lands where the first settlements failed

were subsequently occupied by Polish colonists, whose

descendants remained there and contributed to the formation of

the present-day city of Brusque, an important textile centre

in the state of Santa Catarina.

Conclusion

An attentive reading and interpretation of William Scully's editorials

and various articles published in his newspaper, The

Anglo-Brazilian Times, prior to 1868 suggest that there

was a redefinition of the guidelines according to which

British foreign policy towards Brazil between 1863 and 1870

was conducted. This seems to correspond to the predominance of

the Liberal (Whig) Party in British politics in the

mid-1860's.

On the other hand, such an interpretation complements Leslie Bethell and

Francisco Doratioto's assertion concerning the non-existence

of hard evidence, in primary sources, in support of the idea

that England convinced Brazil and her Triple Alliance partners

(Argentina and Uruguay) to undertake the eradication of a

supposed Paraguayan challenge to British commercial and

strategic hegemony in the South American region of La Plata.

Scully's political propaganda and the problems caused by it

seem to testify to the opposite: the War of the Triple

Alliance would have been detrimental to the execution of

Britain's anti-slavery policy regarding Brazil.

It is interesting to note that in the same

9 October

1866 issue of The Anglo-Brazilian Times that features a

letter addressed to the Clergy of Ireland, whereby the

recruitment of immigrants was requested, a short article was

also published, which decries the outbreak, and continuation,

of the war against Paraguay. In that article, having recalled

arguments brought forward by the followers of Thomas R.

Malthus (1766-1834) to justify the role of wars as inhibitors

of excessive population growth, Scully points out that the

same theory 'loses all the dreadful force of its argument when

applied to the scantily peopled region of the Americas.'

Further on, he considers that 'here at least there should be no

shouldering of each other on the paths of life to necessitate

a war to clear the way.' As he listed every conflict situation

in the

Americas, Scully implies that

Brazil

was responsible for ongoing political problems in Uruguay, a

factor that led to the outbreak of the Paraguayan War: 'we see

a chronic condition of war in an adjoining state fanned by its

powerful neighbor.' And as for the War of the Triple Alliance

itself, he laments that Brazil, Uruguay and Argentina were

'wasting their substance in battling with the little but

aggressive State of Paraguay.' The article continues with a

vehement plea for a co-ordination of efforts by European world

powers and, possibly, the United States, in order to devise a

mediation scheme to bring to an end that armed conflict, since

'so many tens of thousands of their sons' had settled in South

America and established such 'intimate and extended [...]

mercantile relations' with them. Finally, Scully emphasises

the need for such a mediation given the prospect of the

conflict spreading to the whole of the southern continent

'through that unreasonable jealousy which the American

republics display towards the well organized and progressive

immense Empire of Brazil, whose peaceful internal condition

they feel a continuous slur upon their internecine factions.'

As The Anglo-Brazilian Times was the only English-speaking

newspaper in

Brazil at the time, the foregoing pacifist discourse does not

tally with the theory that maintains that the destruction of

Paraguay was of paramount importance to British interests. On

the contrary, if one accepts that Scully's newspaper was

semi-official, partly sponsored by the British Government, and

a vehicle for the conveyance of proposals that expressed the

wishes of British policy makers in regard to Brazil, the

pacifist spirit contained in the article acquires another

meaning. It could be, then, associated with efforts aimed at

boosting European emigration to Brazil as part of a larger

strategy designed to end slavery through massive immigration.

It is not mere coincidence that such an article should

accompany an open letter asking for the Clergy of Ireland's

collaboration in the achievement of that goal. A state of

regional conflagration could only jeopardise those plans, just

as appears to have happened.

This analysis thus suggests that the Irish immigrants who

were brought over from Wednesbury, England, to people the

Príncipe Dom Pedro colony in Santa Catarina, Southern Brazil,

in 1867-1868, played the role of pawns in a lengthy and

cumbersome international chess match opposing Great Britain to

Brazil over the question of slavery - a form of labour

exploitation that the latter rid herself of as late as 1888.

Ireland, in turn, being a British colony at the time, did not

have an independent say on the whole matter, although that

country supplied the manpower with which British plans were to

be carried out.

As for

Brazil,

domestically, the 1868 Cabinet change, triggered by Scully's

editorials, had momentous consequences. The developments that

followed seem to constitute an assertion of the country's

sovereignty, and absolute stubbornness, as regards the task of

addressing the slavery question. Only in 1871 was a Law effectively approved that liberated newborn offspring of slave

women. On the other hand, it consecrated and reinforced the

Brazilian version of the North American Jacksonian 'spoils

system' in the relationship between the Legislature and the

Imperial administration. If one takes it that the Príncipe Dom

Pedro Colony was regarded as a type of foreign threat, the

wholesale substitution of administrative personnel that

followed the downfall of the Liberal-Progressive Cabinet

headed by Zacarias de Góes e Vasconcelos was of crucial

importance to the goal of securing the colony's failure.

Newly appointed Conservative

authorities, who replaced Liberal office holders, actually

refused to help the English-speaking colonists.

Therefore,

that pattern of politico-administrative procedures - and

related institutions - was consolidated in 1868, as a basis

for a lasting framework of social and political relationships.

Derrubadas are still a prominent feature of Brazilian

political life, with everything that they entail: nepotism,

patronage, favoritism, partisanship and, last but not least,

corruption. Upon every major political change in Brazil,

democratic or authoritarian and military-led, the parties and

newly sworn-in authorities replace, with party-members,

allies, friends and relatives, most occupants of federal

administrative entities' leaderships, at nearly all levels.

The same occurs in state and municipal spheres. There are a

few exceptions to the rule, like the Ministry of Foreign

Relations, which is rather immune to partisanship. It looks as

though, up to this day, those newly appointed to positions of

power in Brazilian politics at any given moment since 1868,

were always unwittingly celebrating a small, yet significant,

and unacknowledged, clandestine victory over British - and

Irish - interests: the dismantling of an English-speaking

settlement. |