|

A

topic that has somehow been largely neglected by historians of

the Irish Diaspora is that of onward, or third country,

migration (Marshall 2005: 270, n. 7; 274, n. 8; 276, n. 50).

During most of the nineteenth century North America was the

main destination for Irish migrants with, of course, many of

those heading across the Atlantic travelling via Liverpool.

But with employment opportunities available closer to home, it

is hardly surprising that many Irish migrants avoided the

greater expense, time and hardship of an Atlantic crossing and

instead sought work in the towns and cities of industrial

England. But what remains entirely unknown is how many of

these migrants hoped or expected that their stay in England

would only be as long as needed to raise enough money for an

onward passage to the United States or elsewhere nor what

proportion were successful in re-migrating to third countries.

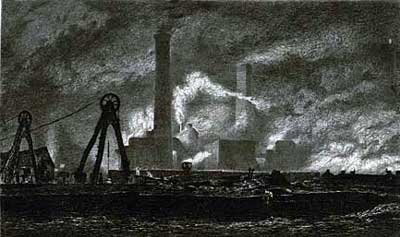

Conditions

for Irish immigrants in nineteenth-century England were

generally grim, with some of the worst experienced by the

community in Wednesbury, in the industrial Midlands. With a

population in 1861 of 22,000, Wednesbury was one of a string

of 'horrid manufacturing towns' (RMR, Vol. 1, No. 5, 28

September 1867) linked together by chains of metal works and

furnaces merging into virtually a single conurbation to form

the iron and coal producing district known as the 'Black

Country'. The area - described by the American consul in

Birmingham as 'black by day and red by night' (Burritt 1868:

3) - both impressed observers for the vast concentration of

its heavy industries within a relatively small area, and also

shocked for the environmental brutality that had been

committed. 'The landscape, if landscape it can be called,'

wrote an anonymous visitor in the 1860s, 'bristles with

stunted towers capped with flame, and with tall chimneys

vomiting forth clouds of black smoke, which literally roofs

the whole region' (SPCK 1864: 12). The soil too was

contaminated, long having been turned 'ink-black' by slurry

and other waste, while the air was 'hot and stifling and

poisoned with mephitic odours' (SPCK 1864: 12). Industrial

noise was constant, often deafening, with an incessant bang

and clang and roar and boom of ponderous hammers thundering

without the pause of a single moment.

It

was to this environment that Father George Montgomery entered

in 1850 when he was sent to Wednesbury to establish a Roman

Catholic mission. Born in Dublin in 1818, the son of a former

Lord Mayor of Dublin, Montgomery grew up in wealthy, staunchly

Protestant, family, an unlikely background for one who would

spend much of his life serving a Catholic community in one of

the harshest corners of industrial England. After taking Holy

Orders in the Church of Ireland and then a period caring for

parishes in Sligo and Dublin, Montgomery was one of many

Anglican priests to convert to Roman Catholicism during the 1840s and

1850s. Admitted to Oscott College, a Catholic seminary in

Birmingham, Montgomery was ordained as a priest in 1849. After

a period of study in Rome, Montgomery returned to England,

lecturing to Catholics in Bilston, a south Staffordshire coal

mining community, from where he was sent to neighbouring

Wednesbury (Marshall 2005: 46).

During the 1840s, Wednesbury's approximately 3,000 Catholic

(overwhelmingly Irish) residents had been left virtually

ignored by church authorities. Due to the flood of

immigrants to England fleeing the famine in Ireland, combined

with an increase in self-confidence amongst English Catholics,

the Roman Catholic Church was stretched beyond its capacity to

meet the spiritual needs of a rapidly growing population. On

arrival in Wednesbury, Montgomery immediately set about

raising money for building work, with St. Mary's Church,

positioned astride a hill-top overlooking the town, opening in

1852. Eager to win local trust, Montgomery saw himself as both

the spiritual and moral protector of the town's Catholic - and

specifically Irish Catholic - community. Shocked by what he

considered to be the miserable and amoral state to which his

parishioners had descended in England, Montgomery felt

obliged, as a missionary priest, to play a central role in the

community to which he had been sent to serve. One of his first

campaigns was to bring a halt to the 'deadly melees' that were

a regular feature of Wednesbury Irish life, the police having

dismissed the community as too 'depraved' to make intervention

worthwhile. Montgomery soon won considerable respect and

affection from his parishioners and, financially forever in

debt and surviving on the barest of necessities, he was

admired, both locally and further a field, for living

extremely modestly (WWBA, 18 March 1871; WRCS,

19 March 1871).

As

the Wednesbury mission became secure, Montgomery concentrated

his attention on education and emigration, expounding his

views of these subjects in The Rev. G. Montgomery's

Register. [1] Published on an

occasional basis from August 1867 and circulated both within

the parish and to friends beyond, the four-page newssheet

featured a mix of local church news, passionate declarations

concerning the position in England of poor Catholics and

extracts from letters that he had received from former

parishioners emigrants living in the United States. Montgomery

was convinced that the British state was utterly untrustworthy

and was possessed with an irreconcilable hatred of the

Catholic religion. Certain that the state's recent interest in

subsidising Catholic schools was to exert control through

financial means, Montgomery called for self-reliance, urging

priests and laity to establish and maintain schools on a

strictly independent basis, setting an example with the

Wednesbury mission school. But while education remained a

major concern, it was to emigration that Montgomery dedicated

much of his energy.

Soon after taking up his position in Wednesbury, Montgomery

began receiving letters from Irish former residents of the

town who had emigrated to the United States, hundreds of whom

had settled in New York, Ohio and Pennsylvania. These letters

frequently contained paid passages for emigrants' friends and

relations who had been left behind in Wednesbury, a fact that

caused Montgomery to observe that his mission was in effect

serving as a depot for United States-bound emigrants.

Recognizing this reality, Montgomery felt justified in

directly intervening in the migration process, taking it upon

himself to investigate possible new destinations and to enter

into negotiations with their agents. Indeed, given the

conditions that prevailed in Wednesbury, not only did he feel

that it was appropriate to assist his parishioners to

emigrate, he felt that it was his duty to do so, declaring:

'We hear our divine Saviour saying, ‘When they persecute

you in one state, flee ye to another,' and we look whither

we may flee to obey this precept' (RMR, Vol. 1, No. 6,

19 October 1867).

Montgomery argued that if the Irish were to remain in England,

it was vital that they improve their position economically as

'without temporal prosperity - speaking of the run of mankind,

and taking people in masses - there can be no spiritual

prosperity' (RMR, Vol. 1, No. 5, 28 September 1867). He

felt, however, even a modest standard of living in England was

an unrealistic goal, with the best that he might achieve would

be 'to dress the wounds of the perishing wayfarer' (RMR,

Vol. 1, No. 5, 28 September 1867). For there to be a hope of

eternal salvation, Montgomery concluded that the Irish must

escape England, to be 'conveyed to a place where [they] may be

thoroughly taken care of' (RMR, Vol. 1, No. 5, 28

September 1867). Acknowledging, however, the Church's

ambivalent attitude with regard to emigration from Ireland

itself, Montgomery was at pains to point out that the

situation of the Irish in England was entirely different:

I

am not disturbing a people who are at home contented and

settled, but I am trying to direct their migrations people who

are on the move in search of a home. To my view the Irish in

England, considered as a body, are like the traveller in the

Gospel, who lay in the way ‘stripped and wounded and half

dead'. The poor people are wounded with five grievous wounds.

They are suffering compulsory and extreme poverty; they are

strangers in the land; they are expatriated strangers, who

have neither country nor home; their progeny is becoming

extinct in the cities and great towns of England; and their

children are apostatising from the Catholic faith (RMR,

Vol. 1, No. 5, 28 September 1867).

Montgomery first considered an Oregon settlement scheme, and

in 1853 he unsuccessfully sought funds to visit the United

States where he hoped to find wealthy Irish-American patrons

willing to finance agricultural settlements in the western

territory. Of his motives behind this plan, Montgomery later

recalled, 'it seemed to me a pity that the expatriated

Catholic peasants of Ireland should die out in the English

towns - a miserable proletarian population without religion or

patriotism.' (RMR, Vol. 1, No. 1, 31 August 1867).

Although he believed that the spiritual condition of Catholics

in the United States was slightly better than was the case of

those in England, he lamented the danger to faith and morals

that Catholics continuously faced in both of these

Protestant-dominated countries. Considering the negative

influences in both England and the United States, Montgomery

was keen to encourage migration to a Catholic country, one

where the Irish would enjoy protection, security of faith and

morals, impossible, agreed Henry Formby, a fellow Catholic

priest and admirer of Montgomery, either in England or in 'the

mixed and often godless society of the United States' (Formby

1871: 10-11).

Rejecting the United States, Montgomery instead looked towards

South America as a possible destination for the Irish poor in

England. How exactly he became such a fervent proponent of

Brazil is not entirely clear but he was clearly attracted by

the Brazilian government's land colonisation programmes that

sought to encourage independent family farms. Montgomery

maintained that agriculture, rather than manufacturing or

industry, was the more 'eligible' way of life, and was

convinced that 'as God had given the earth to the children of

men', it was the necessary work of both 'enlightened

statesmanship' and 'Christian Charity' to assist families of

destitute workers to migrate overseas where they could take

possession of uninhabited fertile lands that were awaiting

exploitation (Formby 1871: 11-14). Montgomery himself recorded

that he began to seriously consider the practical possibility

of Brazil as a destination for emigrants from the British

Isles in 1866 after reading an article in the Standard

(6 April 1866), a London newspaper. 'In no latitude,' the

article extolled, 'can there be discovered greater national

wealth. The surface is enormous, the soil exuberant, the

seaports are magnificent, the navigable rivers unparalleled,

the mines inexhaustible; and yet Brazil pines for people.'

With such a country apparently yearning for immigrants,

Montgomery entered into correspondence with the article's

author, said to be an Englishman who had lived in Brazil for

fifteen years. Encouraged by all that he heard, Montgomery

went on to canvass the opinions of others who had first-hand

experience of the country. Amongst these was Joseph Lazenby,

an Irish Jesuit at the Colégio do Santissimo Salvador in

Desterro, the capital of Santa Catarina, who told him of an

apparently successful agricultural colony in the southern

province largely inhabited by Irish men and families from New

York. Having satisfied himself that Brazil (and in particular

Santa Catarina) was 'a fit place for the settlement of poor

Catholics astray in England' (RMR, Vol. 1, No. 2, 28

September 1867), with support growing for the emigration

scheme - with some going so far as to believe that Brazil

offered the best hope of an Irish cultural renaissance, with

the Irish language being the future language of the settlement

(UN, 15 February 1868) - Montgomery began to take

practical measures to assist his parishioners to emigrate.

Oliver Marshall

[1] The first issue (Vol. 1, No.

1) of The Rev. G. Montgomery's Register is dated 31

August 1867. The only known surviving copies of the newssheet

are held by the Birmingham Archdiocesan Archives, St. Chad's

Cathedral (ref. P303/6/2). The last issue in the collection is

Vol. 1, No. 13, dated 4 July 1868; issue No. 7 is missing.

References

-

WWBA - The Wednesbury and West Country Advertiser

(Wednesbury). |