|

During this time he got in touch with Venezuelan independence

leader Francisco de Miranda, an experienced revolutionary who

had fought against the English in the American Revolution and

served under the flag of the

French

Republic.

Miranda was trying to form a network of young South American

revolutionaries.

De la Cruz finally got the young man back to

Spain, but

more complications followed. Bernardo tried to return to Chile

but his ship was captured by the English and he ended up in

prison in

Gibraltar. Eventually he made his way to Cádiz only to fall

seriously ill with yellow fever. He almost died. By this time

Ambrose had written to De la Cruz that he was no longer

responsible for his son. It is to be supposed that Bernardo's

affiliation with Miranda was by then known in

Madrid.

However, Ambrose died while Bernardo's answer was on its way

to Lima, and surprisingly left his son a generous inheritance,

'Las Canteras,' a sizeable tract of land in Southern Chile on

the frontier with the Mapuche lands where Bernardo had been

born.

From

Landlord to National Leader

For a number of years, Bernardo was more landlord than

revolutionary, although he continued writing letters to

'radical' friends he had met in Cádiz and who now lived in

Buenos

Aires. It was in those days that he befriended one of his most

important mentors, Juan Martinez de Rozas, a former aide to

his father and by then the most powerful man in Southern

Chile, and a strong force in colonial politics. In 1811,

Bernardo had to go to Santiago.

A few months before, due to Ferdinand VII's imprisonment in

Bayonne, France, Santiago's aristocrats had formed a 'junta'

that was to organise a National Congress that would rule in

lieu of the captured king. Bernardo was sent as a

representative of Los Angeles town to this congress. However, his role was small and

menial. He served as a puppet of Martinez de Rozas. He

subsequently got sick again and pretty much disappeared from

local politics.

In the first year or so of the Chilean independence process,

Martinez de Rozas and his party were in conflict with José

Miguel Carrera, a hot-tempered young aristocrat who defied the

establishment and claimed power for himself. Carrera and his

two brothers were more radical than Martinez de Rozas in terms

of leading the revolution. Soon regional tensions between

Santiago and Concepción were impossible to overcome, and

Martinez

and Carrera were on the verge of war. Though O'Higgins put

many of his peasants at the service of Concepción's army,

Martinez awarded him only a minor military position, probably because

his illegitimate origin. O'Higgins' health became increasingly

problematic, and by the end of 1812 he had abandoned

everything and moved back to his estate.

In 1813,

Peru's

viceroy had decided to crush the revolutions in his domains

(although technically Chile was not part of the Viceroyalty),

and sent a professional army to return the situation to the

status quo ante. Bernardo joined the army under the command of

Carrera. He had never received any professional training, but

managed to obtain advice from Irish-born colonel John Mackenna,

also a former associate of Ambrose. Mackenna never trained

O'Higgins, but in a long letter told him who to contact: 'any

dragoon sergeant.'

Now the war was for real. This was no longer a war between

'Chileans' and 'Spaniards,' but rather a civil confrontation

between Chileans who did not recognise any authority from Lima

and Chileans who supported Lima, aided by fresh troops from

Peru and some Spanish-born officers. O'Higgins did not excel

in the first stages of the campaign, although he did fight

bravely at the disastrous siege of Chillán, where the patriots

upheld their positions during a particularly rainy, cold and

muddy winter.

The siege could not make Chillán surrender, dissipating

Carrera's support in

Santiago.

Then came the battle of El Roble. In the middle of the

fighting, Carrera fled while O'Higgins took command and

surprisingly won the battle, allegedly shouting 'To die with

honour or live with glory!.' The

Santiago

junta took command of the army away from Carrera and gave it

to O'Higgins.

In the battlefields things were a little more complicated.

Carrera enjoyed a high level of support among his men, as did

O'Higgins. Bernardo was now assisted by John Mackenna.

Martinez had

died in exile in Mendoza. O'Higgins met Carrera in Concepción,

where Carrera finally surrendered the army command to Bernardo

and left the city. However, en route to Santiago, the

royalists kidnapped and jailed Carrera in Chillán.

Thus the road to victory was opened up for O'Higgins and his

supporters. The war, a savage campaign fought mostly by poor

peasants in rags with no option but to fight alongside their

landlords, had left the land exhausted: no money, no food, no

stock to feed the thousands of men in arms. Both sides signed

a treaty by the Lircay river in May 1814 to end hostilities.

O'Higgins was one of the signatories. In his prison cell

Carrera cursed him.

Feuds:

O'Higgins and José Miguel Carrera

For years, Chilean historians were divided between those who

supported Carrera and those who supported O'Higgins. The

Irish-Chilean eventually won out.

Santiago's

main street is named after O'Higgins, as is the

Military

Academy, and an entire administrative region a few kilometres

south of Santiago bears the name of 'Sixth Region of the

Liberator, General Bernardo O'Higgins.' Bernardo's grave is

situated in front of the Presidential Palace, while Carrera's

skull has allegedly been recently discovered in the basement

of a private house in Santiago.

The hatred between the two men was not extinguished by their

deaths. Supporters of O'Higgins claim that the general was

tricked by

Santiago's

junta, and that he actually wanted to keep waging war because

by May 1814, he thought he could win it. Carrerians despise

O'Higgins because he accepted as one of the treaty's points

the restitution of the Spanish flag and the King's coat of

arms. However the treaty included the liberation of all

prisoners. Soon Carrera and his brother Luis were in route to

Talca, where O'Higgins' army was located, instead of being

shipped to Valparaíso as had been agreed. Carrera was now a

bigger threat to the junta than the royalists, and in July

1814 he staged a new coup d' état that resulted in

Mackenna being exiled to

Mendoza

as O'Higgin's ally.

O'Higgins decided to ignore the royalists in

Southern

Chile and moved the whole patriot army to Santiago, to defy

Carrera. They clashed in the infamous and often forgotten

battle of Tres Acequias, where O'Higgins was defeated, though

he suffered only minor losses. While he was preparing to

attack Carrera the next day, O'Higgins received a message. The

Treaty of Lircay had been ignored by the Viceroy and a

powerful army of professional soldiers fresh from Lima, as

well as volunteers from Chile's southern and staunchly

royalist provinces of Chiloé and Valdivia, had disembarked in

Talcahuano, a few kilometres from Concepción. Carrera always

thought that O'Higgins had had some sort of secret agreement

with the Chilean royalists in order to attack him. But the

Viceroy, who saw all supporters of independence as dangerous

revolutionaries did not make any distinctions. The two men

decided to put an end to their differences and prepare to

battle the enemy, led now by a new royalist leader, General

Mariano Osorio.

|

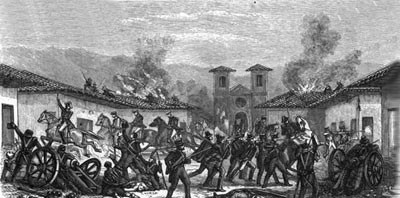

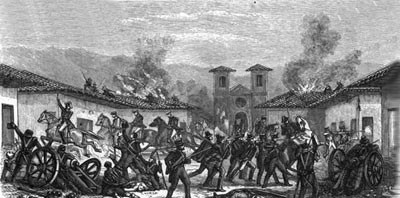

Battle of Rancagua,

October 1814 in: El ostracismo del jeneral D. Bernardo O'Higgins,

by B. Vicuña Mackenna (Valparaíso, 1860).

(Colección Biblioteca Nacional)

|

It was a weak alliance. O'Higgins agreed to renounce his

position as Army commander and serve under Carrera.

Preparations for the mother of all battles followed. The army

was in a disastrous condition. Tres Acequias had destroyed

most of the canons. Carrera raised a group of neophyte

recruits, who in the space of a few weeks became officers.

Most of the veterans had already died or deserted. The battle

was to be in

Rancagua, 90

km south of Santiago a strategic location for Central Chile.

None of its resources had been touched by the war. The

successive waves of patriot divisions sent to the war down

south had still had their own resources when they arrived in

Rancagua, and thus the city and its neighbouring farms had not

been pillaged.

In the

last days of September 1814, O'Higgins was sent to the city,

although Carrera was not completely convinced of the location.

He wanted to fight in Pelequén, a stretch of land comprising

two mountain ranges south of Rancagua. But the patriots had

not had time to fortify the Pelequén hills, and therefore

O'Higgins and Carrera's brother Juan José agreed to wait for

Osorio in Rancagua. |