| Deeply

moved by these revelations, Madden offered the family

what little he could by way of financial assistance. On

the tiny Derry plantation nearby, he discovered

the exact site where, forty years earlier, one of his

uncles, old Garrett Forde, was laid to rest. With a sense

of Shakespearian irony, he observed that the soil covering

the spot had begun to sprout the planter’s beloved sugar

canes. Undoubtedly, the unforeseen encounter with his

Jamaican relatives had a profound impact on Madden, infusing

him with an even greater desire to eradicate slavery in

all its forms (Madden 1891).

Much

to the dismay of colonial officials preoccupied with the

‘sacred rights of property’, as Special Magistrate, Madden

viewed emancipated slaves as British subjects, entitled

to all the protections enjoyed by white subjects under

the law. The duties of the Special Magistrates under the

1833 Abolition Act were ‘extensive but vague’ (Burn 1937:

203); they had exclusive jurisdiction over relations between

apprentices and their former masters. The arduous workload

involved regular tours of inspection on horseback over

a rough terrain, frequently mountainous, covering a radius

of as much as thirty miles.

Duties

included regular visits to jails and workhouses. The Special

Magistrates were required to fix the value of slaves who

wished to purchase their freedom. They also had to find

suitable locations to hold court. When there was a dispute,

Madden insisted upon equal treatment of apprentices in

his court, refusing to hear cases in which coercion had

been used to bring the accused before him. In response,

he faced obstruction by the powerful Council of Kingston,

which maintained its own police force and resented the

imposition of Special Magistrates by the London government.

In

the course of his duties, Madden befriended Benjamin Cochrane,

otherwise known as Anna Moosa or Moses. A native Arabic

speaker and son of a Mandinka chief, Anna Moosa was a

skilled doctor with a practice in Kingston where he administered

popular medicine, demonstrating considerable expertise

with medicinal plants. Madden also struck up a friendship

with Aban Bakr Sadiki (Al-Saddiq), a Muslim scholar and

native of a region bordering Timbuktu, who had been kidnapped

thirty years earlier, transported to Jamaica, and sold

into slavery. Bakr was noted for his Arabic penmanship

and for the accounting ability that became invaluable

to the plantation owner who claimed him as his property.

To Madden he was ‘as much a nobleman in his own country

as any titled chief is in ours’ (Madden 1835: 158). Expressing

his regard for this extraordinary individual, Madden later

wrote, ‘I think if I wanted advice in any important matter

in which it required extreme prudence and a high sense

of moral rectitude to qualify the possessor to give counsel,

I would as soon have recourse to the advice of this poor

negro as any person I know’ (Madden 1835: 158). With some

difficulty, he managed to secure Bakr’s manumission and

passage back to Sierra Leone.

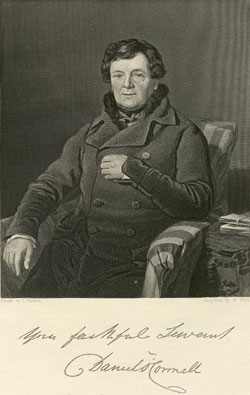

[4]

|

A

portrait of ‘The Liberator,’ Daniel

O’Connell. The publication of Madden’s A

Twelvemonth Residence in the Island of Jamaica (1835)

prompted the Jamaican government to establish a

committee ‘to inquire into the working of the

apprenticeship system in the colonies’ at which

Madden testified that, essentially, the

apprenticeship system was slavery in another form.

O’Connell was a member of this committee.

|

Inevitably,

Madden’s activities led to clashes with employers of apprentices.

On one occasion, when a dispute between a planter and

his apprentice erupted in his court, the irate employer

threatened to have him ‘tarred and feathered’. Without

the support of local law enforcement, his situation became

untenable. Refusing to be intimidated, he was obstructed

and assaulted on a Kingston street, until two other Special

Magistrates intervened and threatened to call in the troops.

Eventually, Madden was forced to resign his position and

return to London noting, ‘I found the protection of the

negro incompatible with my own’ (Madden 1891: 72).

Upon

returning to London, Madden published the two-volume A

Twelvemonth Residence in the Island of Jamaica (1835),

using as a device an epistolary format whose addressees

included prominent literary figures, such as the poet,

Thomas Moore. The book had a considerable effect on public

opinion in Britain (Burn 1937: 221). The work prompted

the government to establish a select committee whose membership

included Daniel O’Connell, ‘to inquire into

the working of the apprenticeship system in the colonies’,

at which Madden testified that, essentially, the apprenticeship

system was slavery in another form. Along with two other

Special Magistrates, he described the difficulties and

abuses inherent in the Jamaican system, but went further

than the others in condemning it as a failure, offering

‘no security for the rights of the negro, no improvement

in his intellectual condition’. His efforts, along with

those of Joseph Sturge and members of the anti-slavery

movement, led to the early abolition of the apprenticeship

system in 1838, two years prior to the date fixed by the

Emancipation Act.

Apart from documenting the inoperability of apprenticeship,

the 1835 work is replete with descriptions of Jamaica’s

flora and fauna based on the author’s observations.

[5]

The appendix to the London edition also provides an insight

into Madden’s views of US policy. Written in the form

of satirical verse, the following lines reflect Irish

opinion as articulated by Daniel O’Connell:

O Hail! Columbia, happy land!

The cradle land of liberty!

Where none but negroes bear the brand,

Or feel the lash of slavery.

Following the signing of the Anglo-Spanish treaty of 1835,

Madden prepared to set sail once again, this time for

Havana, Cuba, the centre of the slave trade. Even before

he set foot on the island in the summer of 1836, the Irishman’s

appointment by the Colonial Office under Lord Glenelg

‘for his merit and character’ (Madden 1891: 75) as Judge

Arbitrator and first Superintendent of Liberated Africans

caused a flurry of diplomatic activity between Cuba and

Spain.

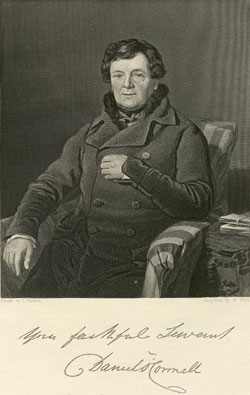

|

A

portrait of Captain General Miguel Tacón y

Rosique. Tacón attempted unsuccessfully to block

Madden’s appointment as Judge Arbitrator,

describing Madden as un

hombre peligroso (‘a dangerous man’) based

on his abolitionist views and activities in

Jamaica.

|

Describing Madden as un hombre peligroso,

(‘a dangerous man’) based on his abolitionist view and

activities in Jamaica, the Captain-General, Miguel Tacón, attempted unsuccessfully to block his appointment.

Madden was also appointed Judge Arbitrator on the International

Mixed Commission Court for the Suppression of the Slave

Trade in Havana under Lord Palmerston at the British Foreign

Office.

[6]

In

accordance with the anti-slave trade treaties, slaves

from condemned vessels were to be liberated and employed

as either free labourers or servants. Since he was charged

with securing the safety of emancipados, or freed

slaves, Madden was set on a collision course with the

ruling saccharocracy. His plan was to transfer the emancipados

from captured vessels to British colonies as free labourers.

Tacón, however, refused to allow the emancipados

to come ashore while awaiting a vessel to transport them

to British colonies, on the pretext that they would transmit

cholera or some other contagious disease. As Madden clearly

pointed out, Tacón had no difficulty allowing enslaved

Africans ashore in chains at out-of-the-way places around

the Cuban coastline. From the perspective of the Captain-General,

only emancipated Africans posed a threat to inhabitants

as ‘pestilential persons’ with their capacity to spread

‘a contagion of liberty’ throughout the island. A confidential

dispatch from Tacón to the Spanish government confirmed

that Madden’s views as an abolitionist unnerved the Captain-General

more than any other concern at that time.

|