|

Irish Landlords in Argentina and their Workers

(1840s-1880s)

John J. Murphy and family

(ca. 1900). |

The arrival in Buenos Aires of 114 Irish

immigrants onboard the William Peile on June 25, 1844

may be viewed as the beginning of the most important

emigration from Ireland to Latin America and, indeed, to any

Spanish-speaking country. The Peile emigration,

though arranged by Irish merchants in Buenos Aires, was not

an organized colonization scheme. To the successful

integration of the immigrants followed spontaneous chains

attracting family members, neighbors, and friends in

Ireland.

Although the number of emigrants to

Argentina is still debated by historians, the latest

estimates include 45-50,000 emigrants during the one hundred

years ending in 1929. At least 50 per cent of the emigrants

did not stay in the country and sooner or later re-emigrated

to other destinations, most notably the US, Australia, or

back to Ireland. Arduous working conditions, accidents, and

epidemics increased significantly the death rate among those

who settled in Argentina, resulting in a 10-15,000

Irish-born population who survived, founded families, and

left descendants who made up the nucleus of the

Irish-Argentine community. Among the latter group, the

success ratio measured in ownership of their means of

production was disproportionate compared to other

communities of the Irish Diaspora, though immigrants in

Argentina from other European regions in the same period

(especially French-Basque and Catalonian) were equally

successful.

Most of the candidates to emigrate were

the children of tenant farmers in the Irish midlands

(counties Westmeath 43 per cent, Longford 15 per cent,

Offaly 3 per cent) and Co. Wexford (16 per cent). They were

lured by the possibility – often imaginary – of becoming

owners of 4,000 acres in Argentina instead of being tenants

of 40 acres in Ireland and, therefore, belonging to a

fanciful Latin American landed gentry instead of to the

Irish farmers' circle. Most of the emigrants in this period

were young men in their early twenties, and later young

women, from families with Roman Catholic background. Upon

arrival they were hired by British, Irish, or Hispano-Creole

estancieros (ranchers) to work in their holdings, and

sometimes to mind their flocks of sheep. Sheep-farming and

the impressive increase of wool international prices in

1830-80, together with convenient sharecropping agreements

with landowners, allowed a substantial part of the Irish

immigrants to establish themselves securely in the

countryside, and progressively acquire sheep and, finally,

land. A few of them, particularly in 1850-70, managed to

acquire large tracts of land from provincial governments in

areas gained from Indian control or beyond the frontier.

However, the vast majority of the Irish rural settlers were

ranch hands, and shepherds on halves or on thirds, and never

had access to landownership. Stories circulated in Ireland

of poor emigrants who became wealthy landowners in the

pampas of Argentina and Uruguay. These stories, frequently

exaggerated, were sometimes fuelled by those who failed to

achieve a successful settlement in Argentina, but did not

want to recognize it at home.

Typically, in the last decades of the

nineteenth century, members of the Argentine landowner class

with Irish origins perceived themselves as English and their

identity was frequently balanced towards British rather than

Irish traditions. Likewise, the middle and lower classes

composed of shepherds and ranch hands in the countryside,

and servants and laborers in the cities, began to be

attracted by Irish nationalist appeals from the church and

the press. The existence in Buenos Aires of two newspapers

owned by Irish-born people, The Standard and The

Southern Cross, may be viewed as a consequence of this

differentiated identities connected to diverse social

groups.

Nationalism in Ireland and in South America (1880s-1930s)

|

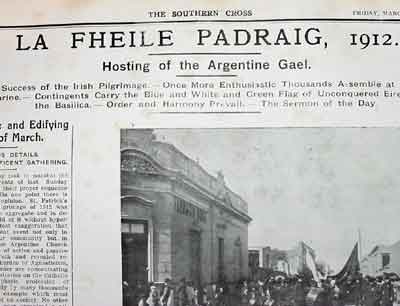

The Southern Cross, 22

March 1912 |

The massive European emigration to

Argentina in 1880-1920 was an incentive to attract further

emigration from Ireland. However, the failure of a

government colonization scheme from Ireland in 1889 known as

the "Dresden Affair" put an end to other official

initiatives. Irish emigrants to Argentina in this period

usually came from urban areas in Belfast, Cork, Dublin, and

Limerick, or from cities in England or the British empire.

Except from those of the Dresden Affair (who were mostly

laborers and servants), the emigrants in this period were

professionals, technicians or administrative employees hired

by railway companies, banks, or meat-packing plants, and

several were from families with a Church of Ireland

background. They rapidly integrated into the Anglo-Argentine

community, following their social and economic patterns,

while some of them actively worked to support Irish

nationalism.

At the turn of the nineteenth century,

most Irish families were living in the provinces of Buenos

Aires, Santa Fe, and Córdoba, as well as in Entre Ríos,

Mendoza, and in distant Patagonia and Falklands-Malvinas

Islands. The trend to move from the camp

(sheep-farmers' lingo for countryside) to the cities was led

by the wealthiest families, thus imitating the residence

patterns of the Argentine landed elite. A majority of the

Argentine-born children of Irish immigrants spoke English as

their mother tongue and learnt Spanish at the school. Those

who were bilingual English-Spanish had a linguistic

advantage and were often employed by British and later US

American companies. Their social activities were shared with

Irish or British relations, being horseracing and later

rugby-football, cricket, and hurling the most popular

athletic activities for men, and lawn tennis for women.

After the years of the World War I (in

which some Irish Argentines fought in British regiments),

there was a new peak of emigration from Ireland to

Argentina, particularly in the period during and after the

Anglo-Irish War of 1919-21 and the Irish Civil War of

1922-23. However, the financial crisis of 1929 as well as

conflicts and political and social catastrophe in Europe and

later in Latin America were serious barriers to emigration.

After 1930 Irish emigration to Argentina virtually came to a

halt. Many Irish Argentines did rather well out of the World

War II. Some thousands of Anglo Argentines (and a few Irish

Argentines) joined the British armed forces, vacating jobs

with British companies which needed to be filled by

bilingual English-Spanish speakers.

Paradoxically, Irish nationalism in

Argentina represented a hindrance to new immigrants who did

not want to be identified with chaos and turmoil in Ireland,

but rather with a perceived notion of British organization

and working habits. Furthermore, the new-rich Irish of

Argentina, and particularly their Argentine-born sons and

daughters, did not want to be considered by the anglophile

Argentine elite as belonging to the same circles of their

poor relatives in Ireland. A social hiatus arose between the

Irish in Argentina and the Irish in Ireland, which gradually

weakened the links among members of the same communities –

even of the same families – in both sides of the Atlantic.

In other countries of the region the British commercial and

investment predominance was gradually occupied by US

companies and diplomacy. By the 1920s most of the families

with Irish surnames in Latin America were considered – and considered themselves – Brazilians,

Chileans, Mexican and others rather than Irish.

Society and State-building: Diplomatic, Religious, and Trade

Links (1930s to date)

There have been some Irish diplomats

gaining experience in Latin America before 1930, including

Robert Gore in Montevideo and Buenos Aires in the 1850s,

Thomas Hutchinson in Rosario in the 1860s, the

Irish-Americans Martin MacMahon and Patrick Egan who

represented the US in Paraguay in the 1860s and in Chile in

1889-93 respectively, and Daniel R. O'Sullivan and the Irish

patriot Roger Casement in Brazil in 1906-11.

The first diplomatic envoy of Ireland to

Latin America was Buenos Aires-born Eamonn Bulfin, who began

working in Argentina in March 1920 after his participation

in the Easter Rising and further banishment from the British

Isles. Bulfin established a contact network in South America

and started an Irish Fund. In 1921, two of Ireland's eight

diplomats, Bulfin and Laurence Ginnell, were based in Latin

America. Patrick J. Little arrived in 1922, being the first

representative of the Irish Free State. The establishment of

formal diplomatic relations with Latin America had to wait

until the end of the World War II. In 1947 Matthew Murphy

was appointed as chargé d'affaires in Buenos Aires, with

Lorenzo McGovern as the first Irish Argentine to be

appointed to the Argentine mission in Dublin in 1955. Irish

diplomatic missions were established in Brazil and Mexico in

1975 and 1977 respectively, and both countries opened

embassies in Dublin in 1991. In other countries, ten

honorary consuls of Ireland operate with the supervision of

Buenos Aires, Brasilia, Mexico, and New York embassies.

One of the most recurrent goals of Irish

trade missions in Latin America is to foster mutual economic

links. However, Ireland is still an almost completely

insignificant market for Latin America. The Irish exports to

Latin America have been increasing over 60 per cent in

1996-2002. In this period, total Irish exports to Latin

America averaged $711 million per annum, though being only

one per cent of Ireland's total exports. Mexico, Brazil,

Argentina, Chile, and Costa Rica are some of the major Latin

American markets for Irish products. Imports from the region

remained at less than one half of the exports (International

Monetary Fund "Direction of Trade Statistics Yearbook 2003"

pp. 270-71). Some Irish companies have performed well in

Latin America. A note-worthy example is Fyffes, an importer

of fruit from Jamaica, Belize, Surinam, Honduras, and

Ecuador into Europe since the 1920s. Powdered milk is an

Irish product frequently exported to Central and South

America. Smurfit has subsidiaries manufacturing paperboard

and packaging products in Colombia, Venezuela, and Mexico.

Guinness Peat Aviation works with Latin American airlines in

many countries. Travel and education are other aspects of

the exchange, with a steady flow of boys and girls going to

Ireland to boarding or day schools since the 1870s and, more

recently, to study English as a foreign language.

Genealogical travel has been exploited sometimes by

Argentine and Irish travel agents, and in the 1970s Aer

Lingus ran a weekly flight to Buenos Aires and Santiago de

Chile. In the latter years Argentina, Brazil, Mexico and the

Caribbean islands are increasingly attracting Irish

visitors.

Apart from the ever-present pseudo-Irish

pubs in many Latin American cities, and the sporadic boom of

Celtic music in Argentina and Brazil, very few

manifestations of Irish popular culture have had much

success in Latin America. University of São Paulo offers a

postgraduate course on Irish literature since 1977. The

Associação Brasileira de Estudos Irlandeses publishes the

ABEI Journal: The Brazilian Journal of Irish Studies,

edited by professors Munira H. Mutran and Laura P.Z. Izarra

since 1999.

|

Irish Spiritan

missionaries in Brazilian favelas, 2004

(www.thespiritans.org) |

Quite apart from official diplomatic

efforts and trade missions in the twentieth century, the

most efficient Irish representatives in Latin America have

been the religious missionaries. In many parts of Latin

America, to be Irish means priests and nuns. Likewise, in

Ireland a part of people's knowledge of Latin America is

derived from notices from these missionaries circulated

through churches. Furthermore, returning missionaries have

had an impact on the Catholic church in Ireland as they seek

to promote the new model of post-Second Vatican social

church frequently associated with Latin America. The

pioneering work of Fr Fahy and other Irish chaplains in

nineteenth-century Argentina, Uruguay, and Falkland-Malvinas

Islands was followed by religious orders. The Sisters of

Mercy, and the Passionist and Pallotine fathers served the

Irish community and followed the pattern of the Irish

missionary movement elsewhere in the nineteenth century –

following the Irish Diaspora or British colonization.

Missionary work with Latin Americans was not established

until 1951-52, when the Columbans opened parishes in Peru

and Chile. Furthermore, lay people were sent to Bogotá in

1953 to establish the Legion of Mary. From Bogotá the work

of the Legion extended to other parts of Colombia and then

to Venezuela, Ecuador, and almost all countries of Latin

America in subsequent years. The Redemptorists established

in Brazil in 1960, the Kiltegans also in Brazil in 1963, the

Irish Dominicans in Argentina in 1965, the Holy Ghosts in

Brazil in 1967, and the Irish Franciscans in Chile and El

Salvador in 1968. The St James Society has worked in Peru

since 1958. Priests and sisters from Cork were sent to work

in Trujillo as an institutional initiative of the diocese of

Cork and Ross. One of these Cork missionaries was Fr Michael

Murphy, who would later become bishop of Cork. The image of

the Latin American church exercised a fascination among

Irish people. In the early 1980s the US policy in El

Salvador and Nicaragua occasioned widespread condemnation in

Ireland. This culminated in the unprecedented wave of

protests which greeted President Ronald Reagan when he

visited Ireland in June 1984.

Gradually, in a process that for the

Irish in Argentina and other countries in the region may

have ended during the Falklands-Malvinas War of 1982, the

Irish in Latin American countries began to perceive

themselves as Argentines, Brazilians, Uruguayans, or

Mexicans with Irish family names. A few among them held some

distinct Irish family traditions. Present-day Latin

Americans with Irish background are estimated by some in

between 300,000 and 500,000 persons. Although some may be

residents of Mexico and Central America, the northern part

of South America, Uruguay, and Brazil, most live in

Argentina. A vast majority among them do not speak English

as their mother tongue nor keep the traditions brought from

Ireland by their ancestors. Inter community marriage during

the twentieth century has allowed most of the families to

assert their local Latin American identities.

Nevertheless, perhaps seeking some kind

of recognition of their Irish identity, in 2002 a group of

about two thousand Irish Argentines submitted a petition to

reside and work in Ireland to the Irish Justice minister

John O'Donoghue. The petition, which was accompanied with a

press campaign targeting Irish politicians and policy-makers

did not obtain a favorable response from the Irish

government. However, it is a demonstration that the links

between Ireland and Latin America which were lost more than

a century ago can still be reshaped to accommodate the

actual needs of Irish-Latin Americans.

Attracting thousands from Latin America to Ireland,

present-day successful Celtic Tiger economy imposes both a

public perception of "best place to live" and a government

policy of restrictive immigration. However, Argentines who

have secured an Irish passport rarely use it to live in

Ireland but rather in other EU countries. The one

significant Latin American community in Ireland are

Brazilians in counties Galway and Roscommon. Most come from

the interior of the state of São Paulo and came with the

experience of working in slaughterhouses in Brazil.

|

References

Davis, Graham. Land! Irish Pioneers in Mexican

and Revolutionary

Texas.

Texas A&M University Press, 2002.

Harris, Mary N., 'Irish

Historical Writing on Latin America, and on Irish

Links with Latin America' in Lévai, Csaba (ed.),

Europe and the World in European Historiography

(Pisa: Editzioni Plus, Pisa University Press, 2006).

Available online, Sezione, CLIOHRES (www.cliohres.net/books/6/Harris.pdf).

[website]

Hasbrouck, Alfred. Foreign Legionaries in the

Liberation of Spanish

South America.

New York: Columbia University, 1928.

Kennedy, Michael. "Mr. Blythe, I Think, Hears

from Him Occasionally" The Experience of Irish

Diplomats in Latin America, 1919-23 in Kennedy,

Michael and J.M Skelly (eds.) "Irish Foreign Policy

1919-66: From Independence to Internationalism"

Dublin: Four Courts, 2000.

Kirby, Peadar.

Ireland and

Latin America: Links and Lessons.

Dublin: Trócaire, 1992.

Marshall, Oliver. English, Irish and

Irish-American Pioneer Settlers in

Nineteenth-Century

Brazil.

Oxford: Centre for Brazilian Studies, University of

Oxford, 2005.

McGinn, Brian. The Irish in South America: A

Bibliography in Website "Irish Diaspora Net"

http://www.irishdiaspora.net (cited February 7,

2005).

McKenna, Patrick. Irish Emigration to

Argentina: A Different Model,

in Bielenberg, Andy (ed.), "The Irish Diaspora"

Essex: Pearson Education Ltd., 2000.

Murray, Edmundo. Becoming "Irlandés": Private

Narratives of the Irish Emigration to

Argentina, 1844-1912.

Buenos Aires: Literature of Latin America, 2005.

Sabato, Hilda and Juan Carlos Korol. Cómo fue la

inmigración irlandesa en Argentina. Buenos

Aires: Plus Ultra, 1981. |

|