|

For instance,

in relation to the breaking off of relations between Brazil

and Great Britain and to the differences between the two

countries, the Irishman derisively condemned the exorbitant

demands of William Christie (ABT, 24 March 1865). On

the other hand, he soon manifested an even greater arrogance

than that displayed by the ex-Minister, filling his articles

with threats and warnings about what would befall Brazil if

his advice and suggestions were not followed immediately.

This can be seen in the ninth issue of the Anglo-Brazilian

Times (8 June 1865). Scully's lead article contains a

weighing up of the results of Brazilian governmental measures

aimed at the promotion of immigration until that point,

together with an appreciation of the possible results of the

delay in addressing appropriately the problem of manpower

scarcity created by the slavery crisis. After beseeching the

Brazilian readership not to be afraid or disdainful of the

European colonist ('foreign immigrants are not the

God-forsaken wretches that Brazilian ignorance and Brazilian

prejudice fain would deem them'), Scully reminds them that

'their tenure of the slave population is slipping rapidly from

out their grasp' and that 'their lands, though fertile and

productive, are valueless without the laborer.'

Demonstrating

affinity with the economic theories propounded by Adam Smith

(1723-1790), Scully then warns Brazilians that 'they must

consider that the laborer is of more value to them than they

to him, that he is the true wealth-creator of the world, and

the merchant, fazendeiro [rancher], and government are

dependent on his labor.' Further, Brazilians should:

remember that

with the European immigrant comes progress, wealth, and

empire; that he brings with him skill, knowledge, enterprize,

and advanced ideas, and has full right to demand, as a

condition of his advent, equal consideration with the children

of the soil he attaches his fortunes unto.

Scully also presents his precise considerations about Brazilian policies

regarding the admittance of immigrants:

Brazil

'tis true votes some 600:000$ annually for the encouragement

of immigration -cui bono? The general and the

provincial governments and individuals have established

'colonies' which they 'direct' and surround with regulations.

They waste their money on these exotic plants that barely

vegetate beneath the fostering care of Directors, Chefs

de Policia, and Juízes de Paz, while the independent

immigration that asks no subventions, no outlay for religious

or profane instructors, no agricultural schools to 'teach the

most improved modes of agriculture and grazing,' and no

salaried 'directors;' that would bring with it intelligence,

enterprize, new ideas, and improved appliances of agriculture,

is afforded no facilities, no information, no encouragement.

Scully then

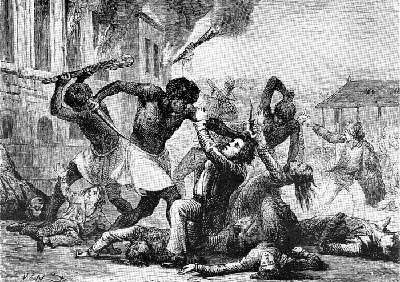

plays up the threat of a general slave rebellion:

Do the

Brazilians not see that their whole prosperity is in danger;

that it now depends solely upon the retention in servitude of

some three millions and a half of negro population; [...] that

no reliance can be placed upon the uneducated slave when once

he is relieved from the stimulus of compulsion [...] that

their lines of railways and river navigation, though largely

subsidized by the national treasury, are commercial failures

from the absence of population along their courses [...] and

do they not see [...] the danger of a second Hayti looming in

the future, facile amidst the mountains, forests, and

unnavigable rivers of this vast and fertile, but almost

roadless region?

In

continuation, as well as pledging support for mass

immigration, his argumentation has aspects that anticipate the

geopolitical strategic thinking that underpinned policies

implemented by the Brazilian military during the twentieth

century:

in fine, do

[Brazilians] not see that, with the grasping and warlike

republics that envelop Brazil, each having to gain largely by

her dismemberment, her existence in her integrality requires

her to keep far in advance in population, wealth, and material

progress; a result attainable only with the concurrence of a

large and persistent immigration?

Therefore, he

states that

To arrive at this result, let the Brazilian government and

the Brazilian people extend a welcoming invitation to

foreign immigrants. Let them be afforded every possible

facility of settlement, and be relieved from the disabilities

and irritating surveillance that disgust them and prevent

development.

Finally,

Scully argues in favour of the North American model of free

immigration:

Let [...]

government lands be granted, or sold at moderate prices, in

tracts of 30,000 to 500,000 braças, each, to real

settlers only. Let a sufficient quantity of such tracts, of

easy access, be always kept surveyed and mapped. [...] Let

every encouragement be given [...] to the formation in Brazil

of Societies like the St. George in New York, to which

immigrants [...] could apply for assistance and advice; and

let means be taken to disseminate knowledge of Brazil in

British and Continental Europe.

He ends the

article with the following assessment:

With these

and similar measures, and perhaps, for a time assisted

immigration, together with liberality from the government and

the people, such a current of immigration might be induced as

would place the prosperity of Brazil upon the only sound and

safe basis -a free and intelligent producing population

warmly attached to their country, their constitution, and

their Emperor.

This line of

argument, taken in its totality, suggests the existence of a

strategy aiming at the extinction of slavery in Brazil by

means of the promotion of mass European immigration. Although

it may perhaps have proved historically inapplicable, the

greatest obstacle to the implementation of Scully's proposals

may have been the man himself. After the first editions of his

newspaper, and prior to 8 June of 1865, he published quite

disdainful analyses and comments on the political and cultural

life of the Brazilian elites. The interpretation of these

pieces lends itself to the perception that the aims of his

initiatives in relation to immigration were to promote an

extensive reform of Brazilian society under the tutelage of

the English. This is corroborated by the indications in

Scully's discourse of a fundamental inspiration for his

proposals: the radical thinker and reformer Jeremy Bentham

(1748-1832), one of the founders of the utilitarian

philosophical movement, also known as Benthamism.

Having in

mind the prospect of implementing this supposedly reformist

agenda, the practice of clientelism (patronage) was

emphatically deplored by Scully, since it inverted the

priorities of parliamentary and governmental activities.

According to him, the working hours of a Brazilian minister

were almost totally devoted to the task of finding posts for

friends, relatives and party affiliates, while legislative and

executive activities were relegated to

second place. This was undoubtedly true, and is attested to by

diverse sources. [11] Scully, though, used the rough edge of

his tongue: addressing the issue of patronage, and how

detrimental it was to the development of the country, one

reads in the editorial of the Anglo-Brazilian Times of

24 May 1865 that 'the life of a Brazilian Minister is a life of

downright slavery'. In other words, slavery was compared to a

cancer that afflicted all of society, from bottom to top,

including the elites. The Brazilian elites' Eurocentric

self-image of enlightenment, combined with their real, or

imagined, ties to the nobility to the Old World and with a

romantic ideal of indigenous ancestry, certainly would not

admit the perceived insolence inherent in this and other

denunciations.

Finally, these charges would not be complete without an appreciation of

the underdeveloped condition of education in

Brazil. Demonstrating yet again what seems to be a utilitarian academic background, the editor of The

Anglo-Brazilian Times believed that the Brazilian

patronage system unavoidably engendered indolence and low

productivity, stemming from the absence of competition for

positions within the public administration. If they were to

remain inactive, the new generations of the Brazilian elites

would be crushed under the wave of progress generated by the

arrival of European immigrants.

Scully begins a discussion by stating that 'true,

our Brazilian boy is not unlearned [...]

still, all his studies are without

an aim, his only view in life is towards the dolce far

niente of a government employment.'

Therefore,

the Brazilian educated classes have through indolence and

pride abandoned to the more utilitarian foreigner engineering,

mining, trades, commerce, and manufactures, and leave the

resources and the riches of their wonderful country

undeveloped until the educated science of some enterprising

foreigner finds out the treasure and turns it to his own

advantage.

Throughout

the article, published on 8 April 1865 under the title

'Education', the threat is reiterated from different angles.

Scully then resorts to a downright derogatory argument in

order to underline the likely outcome:

Again we repeat that mind and body react upon each other and

enervate together, and we warn our Brazilian youth that, if

they suffer to degenerate and become emasculated through their

indolence and contempt for usefulness, they will 'ere long

endure the mortification of being ousted even out of their

present stronghold of the public service, by those other

classes whose pursuits they affect so much to scorn, when once

the energies that win for these their wealth be directed to

the loaves and fishes of the government employ.

Finally, in defence of the incorporation of physical

education into the curriculum of Brazilian schools, Scully

argues that it, 'joined with Western utilitarian science,

makes two hundred thousand Europeans the arbiters of two

hundred millions of the inhabitants of Indian climes'

Brazilians

also had to remember that, thanks to discipline and physical

exercise, 'Waterloo was won at Eton and Harrow'. Eton and

Harrow are two very traditional fee-paying schools for boys in

the United Kingdom, founded respectively in the fifteenth and

sixteenth centuries.

Apparent in the three articles

cited is not only a Eurocentric and Benthamist

(Utilitarianism) tenor, but above all an uncontained British

hegemonic and colonialist vocation. Expressed in these terms,

this involves, paradoxically,

praising ideas of merit, competitive education, and approval

in exams. This naturally clashed with Brazilian social and

political customs, then almost exclusively founded on

privilege and the formation of clienteles. In the articles of

1865 in the Anglo-Brazilian Times it is possible

to perceive, with an antecedence of almost three years, who

was the real antagonist of Caxias.

In

Scully's discourse, then, British expansionism is articulated

along a liberal politico-economic axis, openly opposed to the

slavery system. The destruction of that system, according to

the newspaper, should be achieved by means of free European

immigration. Brazil, however, would ultimately have affirmed

her sovereignty by rejecting both that form of expansionism

and its proposals. As a result, an initiative in which Scully

was directly involved may have been sabotaged. To this end,

the Brazilian elites resorted to a practice similar to the

'spoils' system introduced by president Andrew Jackson

(1767-1845) in the United States in 1828, [12] according to

which only affiliates to the party in power could occupy

public office. In Brazil, that political system was known as 'derrubadas,'

or the wholesale change of occupants of public office, after

every general election. As soon as they were sworn in, they

were able to prevent their opponents' undertakings from

prospering. This was an immediate consequence of the removal

of Zacarias in July 1868, which concurred to produce the

failure of Colônia Príncipe Dom Pedro, in Santa Catarina,

to which Irish settlers had been sent (Marshall 2005: 78). |