|

The

boundaries between the so-called economic core and periphery

of

Europe

have shifted dramatically during the last two decades, as a

consequence of a catch-up by some member states, as well as

the most recent eastward enlargement of the European Union (EU).

Only two decades ago, the European

Economic Community was sharply divided between a rich core and

a poor periphery comprising all Southern European countries

and extending to Ireland.

In 1985, the unemployment rate reached record highs of 16.8%

in the Emerald Isle and 17.8% in Spain. The same year, Gross

Domestic Product (GDP) per head in Ireland stood at 68.9% of

the EU-15 average, whilst Spain’s

was at 71.9%. Accordingly, the two countries absorbed a large

share of European Community (EC) regional development funds as

they strived to converge with the rest of Europe. In spite of

the generosity of these funds, official statistics showed

little signs of convergence during the 1980s. Instead, there

seemed to be increasing divergence between a buoyant core and

a sluggish periphery that struggled to catch up. By those

years, many commentators and even policymakers had developed

the idea of a two-speed Europe as the only way to move forward

in the process of economic integration, and, more

specifically, in order to make the project of a European

Monetary Union viable.

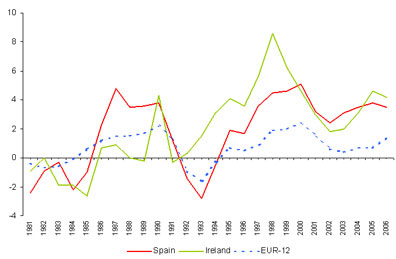

Graph 1: Employment Growth. Annual %

change (Source: Eurostat) |

|

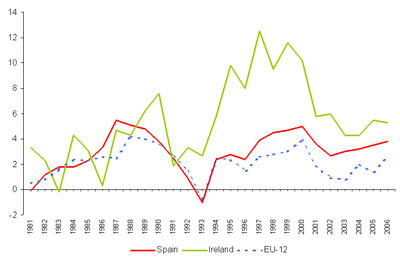

Graph 2: GDP Growth. Annual % change

(Source: Eurostat) |

This picture has changed dramatically during the past

fifteen years. The two laggards of Europe have experienced their most prolonged periods of

economic expansion in their recent economic history. This has

been particularly intense in the case of Ireland, as

demonstrated by certain economic indicators. In 2005, the

unemployment rate in Ireland had plummeted to around 4.4%,

while in Spain

it had also decreased to a record low of 7.8%, close to the

EU-15 average of 7%. Moreover, per capita GDP in Ireland now

stands at around 130% of the EU-15 average, right after

Luxembourg with the highest per capita income in Europe. In

the case of Spain, this figure has reached 91%, its highest

level in the post-World War II period. Graphs 1 and 2 show the

performance of these two countries compared to the average of

the EU-15 group, regarding the labour market and economic

growth. Within the context of what some scholars have

portrayed as a sluggish, rigid and sclerotic Europe, the

exceptional performance of the Irish economy led some authors

to compare it with the growth experiences of some Asian

countries, hence acquiring the epithet of ‘the Celtic Tiger’.

Even though the performance of the Spanish economy has not

reached the levels recorded in Ireland, it nonetheless remains

exceptional both in historical and comparative terms. As a

consequence of these changes, the new economic cleavages

within the EU are no longer characterised in terms of

north-south, but by a west-east division.

The question that arises immediately on examining this

data relates to what explains these experiences and whether

one can find any similarities between the two countries. For,

given the increase in income levels registered in both

countries, there are probably lessons to be learned from these

success stories by scholars and policymakers alike. An obvious

candidate to explain them would be the impact of the process

of European integration in triggering economic convergence

among member states. There are good grounds to support this

argument if one looks at the positive impact of European funds

aimed at creating physical and social capital in these two

countries, or the growth-enhancing effects of macroeconomic

stability brought about by their participation in the European

Monetary Union. However, European integration fails to explain

differences in the growth paths between countries. In this

article, however, I will explore the role of other three

variables whose impact has also been critical in initiating

and sustaining processes of economic development: these are

the role of migration and the transition from emigration to

immigration countries, inward flows of Foreign Direct

Investment (FDI) and national social dialogue. Difficult as it

is to provide magic recipes for growth and job creation, I

argue in this article that in addition to the beneficial

framework provided by EU policies, the three variables just

mentioned have been key ingredients contributing to boosting

employment growth, achieving above EU-average economic

performance and hence reversing the traditional laggard stance

of the two countries analysed here.

|