|

Trois-Rivières Distillery on

Martinique. The estate was owned by the Hooke family

in the eighteenth century.

(Zananas

Martinique) |

In

July 1642, Hooke Castle was attacked by a small

Parliamentary force from the fort of Duncannon, County

Wexford. Manoeuvring two guns ashore from the ship that

had landed them, the assault party proceeded to fire on

‘the castle [for] 4 or 5 hours in vain’. Despite

warnings from the captain of the ship that ‘foul weather

was like to come upon them,’ the men were by this stage

in too great a state of disarray to effect a quick and

orderly retreat. Caught amidst ‘a very great storm and

thick mist,’ the Parliamentarians ‘could not keep

their muskets dry, nor their matches light, neither well

see each other.’ Attacked at that moment by a force of

some 200 Catholic Confederates, almost the entire party

was killed or captured. Only a small number who leaped

from the rocks into the sea, and who avoided drowning in

the attempt, made it back to the ship. Despite this

setback, subsequent attacks on the Castle were more

successful and the remaining members of the Hooke family,

the Castle’s long-time owners and residents, were

allegedly driven out by Cromwellian troops in the late

1640s, escaping or expelled to the West Indies

(O’Callaghan 1885: 328; Hayes 1949: 128).

Despite

the claims made by O’Callaghan and Hayes, no connection

can be made to substantiate a link between the Tower of

Hook (in reality a lighthouse dating from the 1100s) and

the Hooke family. While members of the Hooke family were

indeed to be found on the West Indian islands of

Martinique and Guadeloupe, it is unlikely Cromwellian

dispossession was responsible for their presence. Despite

later misconceptions, the Hookes benefited rather than

suffered from the Cromwellian conquest and settlement.

This article will examine how later accounts, reflecting

and infused with a romantic and strongly nationalist

perception of the Irish abroad, came to turn history on

its head in regard to the Hooke family. The full story is

far more complex and illustrates very well that the

reasons and motivations underpinning migration and

diasporic identity are multifaceted and subject to ongoing

change and transformation. Scholarly undertakings such as

‘The Irish in Europe’ project based in NUI Maynooth

are currently endeavouring to advance the study of the

Irish migrant experience in this context.

Some

of the confusion surrounding the history of the Hookes

stemmed from the activities of another member of the

family, Nathaniel Hooke (1664-1738). Nathaniel Hooke had a

quite remarkable life - born in Dublin, he transformed

from a radical Protestant Whig rebel fighting against

James II in Monmouth’s rebellion of 1685 to a loyal

servant of James in 1688. He metamorphosed yet again in

1701 into a diplomat and soldier of Louis XIV. [2] To suit

his changed circumstances, it seems quite likely that he

constructed this past family connection with Hook Tower.

An early seventeenth century map depicts the lighthouse as

Castle Hooke complete with fortifications (Colfer 2004:

86). A later document by Hooke refers to his possession

and use of a book of maps by cartographer John Speed

(‘The state of Scotland, written by the earl of

Lauderdale in 1690 and sent to me by M. Louis Inese,

Almoner to the Queen’ [with annotation by Hooke], 7 Nov.

1705, (A.A.E. CP Angleterre, supplemental, vol. 3, f.

277r). [3] Hooke wrote in praise of the usefulness of the

atlas in 1705, one year before he applied for

naturalisation as a French subject. For a man seeking to

prove his noble ancestry, the existence of an extant Hooke

Castle with suitably impressive battlements hinting at the

past martial gloire of the family must have been a

godsend. The naturalisation papers submitted for

registration in the Chambre des Comptes in January 1706

traced the origins of the Hookes back to Eustache de la

Hougue and the Norman invasion of England in 1066

(Bibliothèque Nationale, MSS Dossiers Bleus 59, f. 9351).

In 1172 a descendant, Florence de la Hougue, allegedly

accompanied Henry II to Ireland, established himself near

Waterford and anglicised his name to Hooke. The town which

he founded was called Hooke-Town, but unfortunately (if

perhaps conveniently), this bourg had been eventually

inundated by the ocean. The only remaining remnant of the

settlement was the family chateau, still bearing the name

of Hooke Castle. The document then skipped without further

detail directly from the twelfth century to Nathaniel

Hooke himself.

|

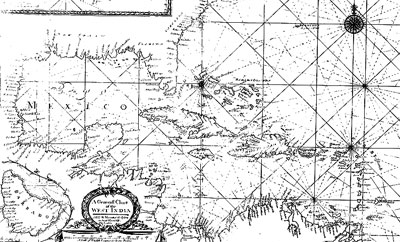

Anonymous, The English pilot.

describing the sea-coasts, capes, head-lands,

rivers, [...] from Hudsons-Bay to the river Amazones,

etc.

(London: Printed for John Thornton and Richard

Mount, 1698) |

A

pedigree of the family contained in a French genealogical

guide draws on and echoes much of the account given in the

naturalisation document (De Saint-Allais 1872: 19-22).

Intriguingly, however, it then proceeds to add new

information fleshing out the rather skeletal family tree

presented in the original source with a much more detailed

genealogy. In this version, we learn of the same claimed

descent from Eustache de la Hougue’s arrival in England,

to Florence de la Hougue’s journey to Ireland. From this

point it jumps four centuries to arrive at another

Eustache Hooke, of Hooke Castle, County Waterford. His

existence is unconfirmed by other documentation. He is

said to have lived in the 1590s and to have been married

to Helen O’Byrne of County Wicklow. His son is named as

Thomas Hooke (of Hooke Castle), who married Eleanor

O’Kelly from Aughrim in County Galway (or possibly of

Aughrim, County Wicklow). Partial veracity of the document

is confirmed by the inclusion of Thomas Hooke,

Nathaniel’s grandfather. Independent documentation

confirms his existence, though not his place of birth, and

the feasibility of his being born in 1590s (Twenty-sixth

report of the deputy keeper of the public records and

keeper of the state papers in Ireland 1894: 428). There is

no evidence connecting him with Hooke Castle.

It

is interesting to note that both of these early Hookes are

purported to have married women from prominent Gaelic

Irish families. Such a connection with Gaelic nobility

would have served Nathaniel Hooke’s purpose in 1706 by

strengthening his claim to noble status in French eyes. It

may also have gained him greater acceptance in Irish émigré

circles in Paris. Significantly, Hooke made no mention

that his grandfather Thomas Hooke had been mayor of Dublin

in 1654, during Cromwellian rule, nor that he had been a

lay elder of a radical Protestant church in the city.

While this would have testified to the family’s status,

it would also have highlighted unwelcome links with

Parliamentarianism and radical Protestantism in the 1640s,

1650s and 1660s. Hooke would appear to have suppressed

this aspect of his past by constructing the alternative

origin centring on Hooke Castle/Hook Tower.

Nathaniel

Hooke was far from unusual in attempting to embellish

retrospectively his ancestry, to mask the foundations of a

rather too hasty social ascent. Many first and second

generation arrivistes in Ireland, England and France spent

much time and not a little money avoiding the stigma of

being seen as a parvenu in the ranks of nobility.

‘Parvenus ... sought to cover their sometimes unsavoury

and usually shadowy backgrounds with a veneer of

antiquity’. Similarly, ‘members of the displaced élites

of Old Ireland, adrift on the continent, clutched at

pedigrees [which] comforted by reminding them of what they

had forfeited, and buttressed requests for fresh

ennoblement’ (Barnard 2003: 45-51). That even a man as

eminent in the hierarchies of the French church and state

as Cardinal Richelieu felt the need for a sympathetic

appraisal of his pedigree demonstrates that the weight of

authority and legitimacy attached to the prestige of

lineage was no mere foible (Bergin 1997: 12-13). The

consequences of having the legitimacy of claims accepted

could be great. For a man in Richelieu’s position in the

highest ranks of the elite, for example, an illustrious

past served to cast his rise to power in a natural light

and reinforce his hold on the most influential offices of

state. To those in Hooke’s position, strangers in

France, far below les grands on the social scale, the

benefits of a distinguished ancestry were more practical.

Economically, the acknowledgement of noble status was

vitally important in avoiding taxes and making the

financial position of émigré families more secure.

Socially, it provided an entrée into the decidedly and

determinedly select world of the French nobility.

|