|

Christmas Carnival in Montserrat

(Jonathan Skinner, 2000) |

The Caribbean was the

first American region to come to the attention of

sixteenth-century Europeans. It was here that they at

first marvelled at the pristine beauty of the New World,

were puzzled by the 'strange' Arawak and Carib natives,

lorded it over the indigenous people and their countryside

in the name of religion, civilisation, and mercantile

expansion. They thereby set in motion the largest

trans-oceanic migratory movement in the history of the

world. The pursuit of riches and fame lured enterprising

people from throughout the 'Old World,' fascinated by the

unique languages, spiritual beliefs, and cultural

artefacts of the people of the 'New World'. While it is

tempting to describe this process using modern-day

multicultural clichés like the 'melting pot' ideology of

the United States or 'mestizaje' in Latin America, it must

be remembered that intense friction accompanied the

post-1492 re-settlement of the New World.

The newcomers brought

with them their centuries-old quarrels, and these were

played out in the Antillean archipelago in the shape of

inter-imperial competition and warfare. These carry-overs

from Old World politics, in turn, would influence the

various ethnic, religious, and racial groups that came to

be a part of the re-settlement of the Americas. The

Caribbean and its surrounding littoral exemplify this

legacy. Perennial clashes between Spain, France, England,

Denmark and Holland, the five leading European countries

whose subjects carved out colonies there, have

characterised much the history of this region over the

past five centuries. Even Sweden, which at one point

occupied the tiny island of Saint Bartholomew, was

involved in these economic and territorial battles.

Although the region-wide

violence perpetrated by pirates, privateers and armed

military expeditions, who raided, pillage and killed is

now largely behind us, it has been replaced by another

type of discord: the politics of representation. The

area's present-day historiography, particularly in

relation to the colonial period, mostly focuses on the

Spanish, French, British, Danish and Dutch settlers, and

their various attempts to gain the upper hand. Colonists,

fortune-hunters, adventurers, clerics, voyagers, coerced

labourers, prisoners, religious dissidents and mercenaries

from other parts of Europe who also had a role in the

demographic, economic and political evolution of the

Antillean archipelago, are generally marginalised or

silenced.

The Irishmen and women

whose varied experiences are featured in this special

edition of Irish Migration Studies in Latin America

are certainly some of them. With the possible exception of

the Irish association with the eastern Caribbean island of

Montserrat, they are not in the mainstream of academic and

popular discussions of Caribbean Studies. It is hoped that

the essays that follow will shed some light on their

voluntary or compulsory arrival, successes and failures,

misfortunes and strokes of luck, virtues and shortcomings,

contributions and blunders, in short on their 'lived'

experiences.

Perhaps one of the most

revealing findings in this collection is the fact that the

Irish diaspora in the Caribbean was not limited to any one

historical period, group of individuals, or geographical

area. Their presence in the region stretched across time,

from the indentured servants in the 1650s to mercenaries

and freedom fighters in the early nineteenth-century

Spanish American wars of independence. Unlike many other

European colonists, who generally came as single men, one

finds both Irish men and women among the pioneers. Some,

like Byrne's John Hooke, arrived voluntarily; others

crossed the Atlantic under duress, like the transported

and forced labourers studied by Rodgers.

Most European settlers

on the islands confined themselves to one or another

island or group of islands, hence the modern-day

expressions Hispanic Caribbean, French Caribbean, British

Caribbean, and so on. The Irish, on the other hand, looked

for and found new homes wherever opportunities or other

circumstances took them. They resided on practically all

of the islands of the Caribbean and circum-Caribbean zone,

as demonstrated in the papers by Rodgers, Anderson, Power

and Chinea, among others. Some of them were undoubtedly

trans-colonial, multilingual, and highly adaptable to

changing environments.

|

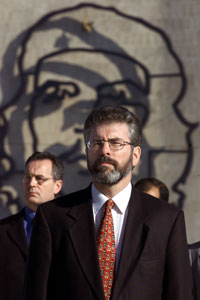

Sinn Féin leader Gerry Adams at the

Plaza de la Revolución, Havana, during his visit to

Cuba on 16-19 December 2001.

(José Goitía/AP, 2001) |

The Irish also helped to

shape the demographic, social, economic and political

evolution of the areas under study. Early on, Irish

servants and religious dissidents comprised the bulk of

the white population of the British Caribbean. When the

islands made the transition to sugar cultivation, and

Africanisation set in, this numerical advantage faded

away. Since the presence of whites now became a matter of

public safety, some of the Irish exploited this shift to

their advantage whenever possible, by seeking or demanding

access to the more prestigious positions of master

artisans, overseers and planters.

In some cases, as shown

by Power, Irish people took leading mercantile positions

in the expanding world of transatlantic trade. Others

escaped from servitude or defected to England's Catholic

rivals, especially France and Spain. In Cuba, Irish

railroad workers became part of the plantocracy's

unsuccessful 'whitening' scheme, as described in Brehony's

article. Politically, the vital roles played by the

O'Reilly-O'Daly team in revamping defences in the Puerto

Rican capital of San Juan, as examined in Chinea's

article, or John 'Dinamita' O'Brien during the Cuban

insurrection of the 1890s, analysed in Quintana's article,

are also acknowledged in this volume. They are but a few

examples of a long tradition of Irish military presence in

Spain and its American colonies.

Finally, the Irish

impact in the region went beyond their physical activities

as servants, planters, merchants and soldiers. Attempts to

draw comparisons between the colonial experiences of

Ireland and the Caribbean have also sparked the creative

energies and imagination of writers. Two examples in this

volume are Tewfik's insightful deconstruction of Lorna

Goodison's poem, 'Country Sligoville', and Novillo

Corvalán's original search for a literary kinship in the

works of Derek Walcott and James Joyce. Their work shows

the enduring cultural, linguistic and political

cross-pollination resulting from the Irish presence in the

Caribbean, one that challenges the notion of discreet

colonies or nations evolving in relative isolation.

Instead, the authors show how writers in both the

Caribbean and Ireland see or have come to grips with their

common experiences with servitude, oppression and forms of

colonialism.

Jorge L. Chinea

Wayne State University |