The

Irish Road to South America

Nineteenth-Century

Travel Patterns from Ireland to the River Plate

|

Page

2 |

|

Writers

at the turn of the century had a particular fascination with

some enclaves of the Royal Canal. ‘The Irish/Argentine William

Bulfin, the intrepid traveller and editor of The Southern

Cross approached Abbeyshrule [Co. Longford] by the line

from Tenelick. He stopped to chat to a denizen of the locality

and realised to his astonishment that he was in the famous

Mill Lane of which he had heard many a time and oft far away

on The Pampas in corral or chiquero when the sun-tanned

exiles of Longford and Westmeath recalled some story of Abbeyshrule

and its Mill Lane’ [McGoey 1996].

Baggage

used by the emigrants would have been trunks and boxes for

well-off travellers and simple bags for the poor emigrants.

Kate Connolly in You'll Never Go Back mentions that

her party’s baggage was a couple of trunks, and that Dick

Delaney, the sign painter, 'painted our names on both. I remember

how just the two boxes looked, standing on the kitchen floor

before the dresser, with "The Misses Connolly – Buenos

Ayres" on one, and "Miss Dwyer – Buenos Ayres"

on the other. [...] Nancy had said she wanted to see her name

on a trunk, no matter whose trunk it was, so we agreed, and

she was wild with delight at the sight of it' [Nevin 1946:

12]. |

|

The Royal Canal.

Scally's Bridge in Abbeyshrule, Co. Longford (2002)0 |

|

|

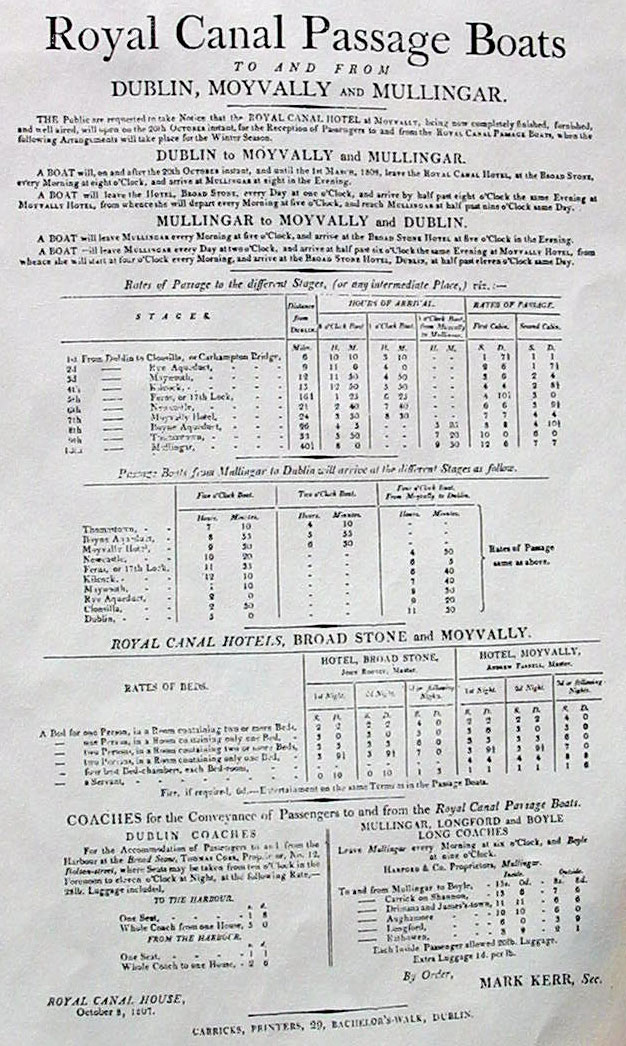

Timetable

from 1807 (Clarke 1992) |

|

In

October 1848, heralding the decline of the importance of the

Royal Canal, the Midland Great Western Railway Company (MGWR)

reached Mullingar and in August, 1851, the line extended to

Athlone. The railway age ‘signalled the demise of the canal.

In 1845 the railway company purchased the entire canal for

£298,059, principally to use the property to lay a new railway.

It was legally obliged to continue the canal business, but

inevitably traffic fell into decline. Passenger business ceased

totally within a few years and by the 1880s the annual goods

tally was down to 30,000 tons’ [O.P.W. Waterways 1996: 19].

By

November 1855, the railway reached Longford. From 1848 onwards,

the railway replaced the canal as the main mean of transport

to Dublin. In the 1850s, emigrants travelling on the MGWR

line had a choice of four trains daily to Dublin. The number

of trains to the capital increased in the 1860s with the extension

of the line to Galway and Sligo. Journey time to Dublin was

around two hours. Those who travelled by third or fourth class

would have had an uncomfortable journey: the 1850s fourth

class carriages had neither heat nor sanitation, and were

little better than cattle trucks, sometimes without seating.

In

the Midland Great Western Railway line, the stations between

Mullingar and Dublin were Killugan, Hill of Down, Moyvalley,

Enfield, Ferns Lock, Kilcock, Maynooth, Leixlip, Luran, Clonsilla

and Blanchardstown, with a total distance of 83 kilometres.

A timetable sheet of December, 1853, includes six daily trains

(arriving at Dublin 5.15 A.M., 9.45 A.M., 11.30 A.M, 2.00

P.M., 9.00 P.M., and 10 P.M.) and two Sunday trains (arriving

at Dublin 5.15 A.M. and 10.00 P.M.). Fares were 8s (first

class), 6s-6d (second), 4s-9d (third), and 3s (fourth). Most

of the emigrants ‘would have purchased third of fourth class

tickets to Dublin’ [Illingworth 2001]. |

(Ulster Folk and Transport Museum) |

|

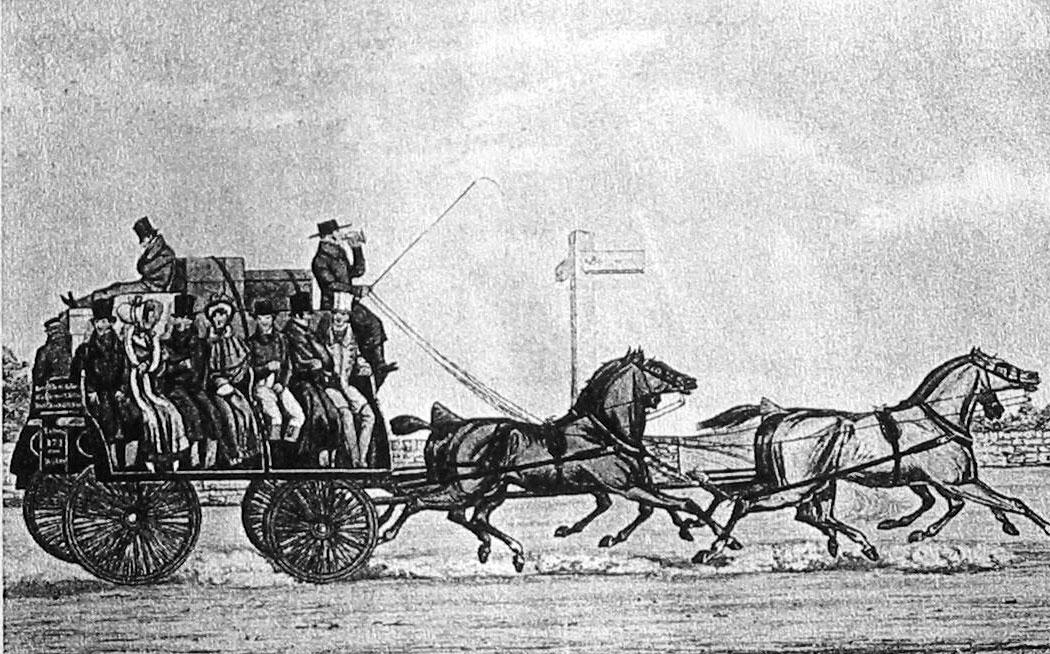

| Those

emigrants who lived at a distance from the railway would

take a coach to reach the rail station. The village of

Ballymore, which was the epicentre for the Midlands emigration

to South America, is about twenty kilometres west of Mullingar

on the now road to Athlone. The nearest railway stations

‘were Athlone and Mullingar, and stage coaches passed

through Ballymore on the way to Mullingar and Dublin’

[Illingworth 2002]. By the late 1840s, Bianconi

coaches, [5] each capable of carrying up to twenty passengers,

provided the means by which emigrants could reach Longford,

Mullingar and Athlone from the countryside, and from the

small rural villages and townlands of Westmeath and Longford.

Smaller stage coaches travelling directly from Athlone

and Mullingar to Dublin were also used by emigrants up

until the 1850s. Horse-drawn |

|

Mullingar Railway Station (2002) |

|

stagecoaches moved at about twelve kilometres per hour, with

frequent stops to rest both horses and passengers, ‘who sometimes

needed it more after long bumpy rides over rough roads’ [O’Cleirigh

2002]. A traveller who went by coach from Strabane to Enniskillen

in 1834 tells that:

|

At first it drove on at a rapid

rate, carrying about twenty-eight passengers, ten inside

and eighteen on the outside, noisy and inebriated fellows…

My feet had got numb with cold… When we had arrived

within two yards of Seein Bridge, between Strabane and

Newtownstewart, the lofty vehicle was thrown into the

ditch, within two yards of a dangerous and steep bridge.

If the vehicle had advanced about three yards further

we would have been dashed to death [O’Cleirigh 2002].

|

|

(Ulster Folk and Transport Museum)

|

The

Bianconi’s ‘Car and Coach Lists’ of 1842 includes the timetable

of the stagecoaches connected with the Royal Canal boats to

Dublin, and intermediate stages. From Ballymahon, the coach

departed 4.08 A.M. arriving at Mullingar at 6.11 A.M. |

(Ulster Folk and Transport Museum) |

|

In

the 1850s, William Mulvihill of Ballymahon, Co. Longford,

was the agent for the River Plate Steamship Company in

the Midlands. [6] Prospective emigrants would buy their

tickets from Mulvihill’s grocery store. From Mullingar,

the emigrants could book a direct rail plus boat ticket

to Liverpool for £2-2s. ‘The fact that emigrants [to South

America] were advised to bring a revolver as well as a

saddle may not have deterred farmers who had been forced

to protect their stocks from starving labourers’ [O’Brien

1999: 55]. This would indicate that some of the emigrants

bound to Argentina – who were able to pay a high fare

to South America – were also able to ride a horse, a skill

that would be very useful for them in the Argentine pampas.

|

| |

|

[5]

Named after Charles Bianconi (the king

of the Irish roads), who started the first Irish mail

coach service in 1815, beginning from the Hearn’s hotel in

Clonmel, Co. Tipperary, to Thurles and Limerick. By 1825,

Bianconi had 585 route miles and two decades later he had

trebled. In 1836, long cars with twenty passengers capacity

were added to the service. He had rivals but, where they often

competed with the canal boats, Bianconi tended to run connecting

feeder services, a move which enabled him to outstay many

other operators.

[6]

Under ‘Mulvihill,

William’ there are two entries in Leahy 1996: 166 (County

Longford Survivors of the Great Famine: a Complete Index to

Griffith’s Primary Valuation of Co. Longford 1854), and

one in Leahy 1990: 151 (County Longford and its People:

an Index to the 1901 Census for County Longford). |

|

|

|

|

|