|

|

The Emperor Pedro I of Brazil |

Recruitment in

London

and Liverpool presented few problems. There were a sufficient

number of hardy souls willing to exchange the chilling fogs of

the European winter for service in the sun, good pay and prize

money. The salary scales of the Brazilian Navy may have been

generous for seamen, but for officers they were less so. £8 a

month for lieutenants and £5 for sub‑lieutenants were only

two‑thirds of the rates paid in the Royal Navy, but the

comparison meant little to men who had long since abandoned

all hope of ever serving again under the British flag.

Furthermore, the contracts offered by the Brazilian Agent were

attractive. Each officer was to sign on for five years - if at

the end of that time he remained in the service he would

receive an extra 50 per cent in addition to his normal salary;

if he returned to Britain he would receive Brazilian half‑pay

for the rest of his life. Free passages were provided and pay

was to commence from the date of embarkation.

[4] All the

officers recruited by Thompson had previously served in the

Royal Navy. Vincent Crofton, Samuel Chester, Francis Clare and

Richard Phibbs had been midshipmen but had passed the

examination for lieutenant and were appointed as such. The

fifth, Benjamin Kelmare, had served with Cochrane in Chile

where he had been wounded in the attack on the Esmeralda.

He was commissioned as a commander.

[5]

The first recruiting exercise was a complete success and was

conducted in strict secrecy to escape the attentions of the

British authorities and the Portuguese consuls. To avoid

detection under the Foreign Enlistment Act of 1819, Brant

maintained the fiction that the recruits were settlers

emigrating to Brazil, and carefully described the seamen in

official documents as 'farm labourers' and the officers as

'overseers'. The authorities must however have colluded in

this deception since in dress, language and gait, seamen were

such a distinctive group that they could not have been

mistaken!

At the end of January 1823, the first party of 125 men and six

officers left Liverpool on the Lindsays to be followed

three days later by a second group of forty-five seamen who

left London on the Lapwing.

[6] On arrival in Rio, the

officers were distributed among the most powerful ships in the

squadron [7] while the seamen were signed on and allowed

ashore for the first time in six weeks. Within a few hours of

exposure to all the pleasures of a foreign port, the majority

were gloriously drunk. When some officers complained to the

Empress, it is reported that she laughed and said 'Oh, 'tis

the custom of the north where brave men come from. The sailors

are under my protection; I spread my mantle over them!’[8]

Lieutenant Phibbs was found to be medically unfit, but the

vacancy was easily filled by the recruitment of John Nicol and

William Parker, Mates respectively of the Lapwing and

the Lindsays. [9]

Brant reported on the success of his efforts with undisguised

satisfaction. The cost of recruitment in

London

had been reasonable and the men had accepted monthly pay of

just £2. In Liverpool on the other hand, the 'perfidious'

Meirelles had ignored his instructions and had not only

offered £5.50 a month but, disregarding the need for secrecy,

had 'criminally and unnecessarily' signed a contract to that

effect. Brant reported hotly that on being reprimanded on the

excessive offer of pay, the Vice‑Consul had merely retorted

that when the men were in

Rio

and the government could pay what it liked.

[10]

|

The

entrance to the Bay of Guanabara showing the Sugar Loaf

(Naval Chronical, 1808) |

Nevertheless, news of Portuguese reinforcements continued to

arrive and when in March, officers of the HMS Conway,

recently returned from

Brazil,

reported that the navy was still hampered by a lack of men,

Brant determined to launch a second recruiting campaign.

[11]

He and Meirelles went into action, and within six weeks had

found 265 seamen and fourteen officers, all of whom had

previously served in the Royal Navy. This time the officers

were engaged through the agency of Captain James Norton, a

34-year-old English officer with aristocratic connections who

had fought in the Napoleonic Wars with the Royal Navy and had

then served with the East India Company. Norton was

commissioned as a frigate captain, while five of his

companions ‑ John Rogers Gleddon, George Clarence, Charles

Mosselyn, Samuel Gillett and Raphael Wright ‑ became

lieutenants. The more junior recruits ‑ Duncan Macreights,

George Broom, George Cowan, Ambrose Challes, Charles Watson,

William George Inglis, and James Watson ‑ were appointed as

sub‑lieutenants. [12] Together with officers and seamen, the

party also included petty officers and boatswains as well as

thirty-one young men who signed on as Master’s Mates or

Volunteers in the hope of eventually gaining promotion to the

quarter deck. They were not disappointed; within a year,

almost all had been appointed as sub‑lieutenants.

[13]

Having staffed and fitted out his ships, in April 1823

Cochrane led the Brazilian Navy out of Rio de Janeiro on a cruise of astonishing audacity

and success. In a campaign of only six months he blockaded and

expelled a Portuguese army and a greatly superior naval

squadron from its base in

Bahia, then harried it out of Brazilian waters and across the

Atlantic. He then tricked the Portuguese garrisons into

evacuating Maranhão and Belém, leaving the

northern provinces

free to pledge allegiance to the Empire. By the end of the

year, the country had rid itself of all Portuguese troops and

was, to all intents and purposes, independent. If 1823 was the

year of victory for the Brazilian Navy, 1824 was the year of

consolidation. Cochrane’s men first deployed themselves in

preventing any Portuguese counter-invasion, then co-operated

with the army in defeating a dangerous north-eastern rebellion

known as the Confederation of the Equator.

[14]

The War of Independence had also seen a dramatic increase in

the size of the Brazilian navy. In 1823, it had comprised just

twenty-eight warships and schooners carrying a total of 382

guns. A year later as a result of captures and further

purchases it had grown to forty-eight vessels with 620 guns.

The expansion was spectacular, but it meant that once again

the government was short of junior officers and men. The

experience of foreign recruitment in 1823 had however been

highly satisfactory. Desertions had been minimal; of the

fifty-eight British officers or aspiring officers recruited in

England and locally, only thirteen had deserted their posts.

Crosbie had left with Cochrane to seek their fortunes in

Greece; James Watson and Samuel Gillett had deserted; Joseph

Sewell, Thomas Poynton and John Rogers Molloy had been

dismissed; Commander Benjamin Kelmare and Sub-lieutenants

Blakely and Macreights had quietly left the service; and

Lieutenants Chester, Challes and Mosselyn had died or become

invalids, a relatively small proportion in view of the

diseases prevalent on overcrowded ships in the tropics.

|

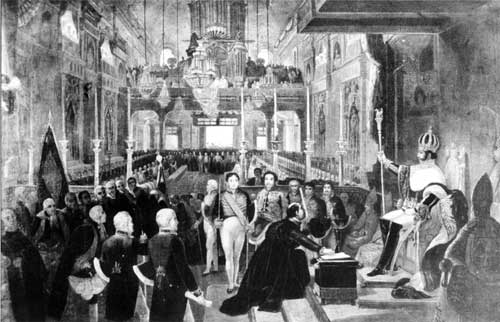

The Coronation of Pedro I in 1822

(J.B. Debrett) |

Encouraged by its initial success, the Brazilian Government

mounted a second recruiting campaign in 1825. General Brant in

London was ordered to find eight hundred seamen and eighteen

officers below the rank of commander and to buy two frigates

and two armed steamships.

[15] This time, in spite of pay

increases for both officers and men, the task was more

difficult. Brant and his new colleague Gameiro managed to find

eleven officers, but this time only two ‑ Lieutenant Thomas

Haydon and Midshipman Louis Brown, cousin of the

Irish-Austrian General Gustavo Brown who had transferred to

the Brazilian service ‑ were British, the rest were French or

Scandinavian. [16] Seamen were easier to find, and by the end

of 1825, about four hundred were on their way – just in time

for

Brazil’s

war with Buenos Aires. [17]

The war between

Brazil

and the United Provinces of the River Plate was fought out by

small squadrons in the channels and mud‑flats of the river and

by individual warships engaging the Argentine privateers who

were unleashed along the Brazilian coast. One of the

curiosities of the war – in which British trade was a major

victim – was that the navies of both sides were substantially

commanded and manned by men from England, Ireland and

Scotland. On the Brazilian side Commodore Norton, who

lost his arm in the process, commanded the inshore squadron in the river and led it to

minor victories, backed by ships commanded by Bartholomew

Hayden, Francis Clare and William James Inglis. John Pascoe Grenfell, Thomas Craig and

George Broom all distinguished themselves as commanders in

single ship actions. Not all survived; Lieutenant John Rogers Gleddon and Sub-lieutenant Charles Yell were killed at sea,

while Captain James Shepherd died leading a disastrous attack

in

Patagonia. The navy quietly dispensed with the services of

four more, Sub‑lieutenant Gore Whitlock Oudesley and

Lieutenant David Carter for being drunk during the capture of

their corvette in 1827; Lieutenant Vincent Crofton,

graphically described by his commanding officer as 'a madman

and a drunkard'; and Commander Alexander Reid for sheer

incompetence. In 1827, Sub‑lieutenant Robert Mackintosh seized

control of the schooner he commanded with the help of

Argentine prisoners and sailed it to

Buenos Aires.

There he sold it to the government and pocketed the proceeds.

The war inevitably served as a powerful stimulant to the

growth of the Brazilian Navy By 1828, it was the biggest in

the Americas and had grown to one ship-of-the-line, nine

frigates, sixty-six smaller warships and two armed steamships

carrying 875 guns. The personnel consisted of about 8,400

officers and men, of whom no less than 1,200 were natives of

Britain and Ireland. [18] The advantages of this arrangement

were clear, yet so too were the problems. There had been, for

example, instances of groups of captured seamen changing sides

rather than face unpaid imprisonment. A minor revolution in

1831 and the abdication of Emperor Pedro brought a government

to power in Brazil which believed in economies and

retrenchment. The navy which was cut to one-fifth of its

former size and was firmly recast in the role it was to play

for the rest of the century, that of regional policeman and

coastguard. When it eventually went to war, first against the

Argentine dictator Juan Manuel de Rosas in 1852, and then

against Paraguay as part of the Triple Alliance with Argentina

and Uruguay in 1865, its field of glory lay not on the ocean

but in seizing control of the great internal rivers of South

America.

|